From Jules Verne to Maurice Renard : the precursors

The text in which Maurice Renard attempted to define the “merveilleux-scientifique” in 1909, is a milestone in the history of literature. In it, he affirms the existence of a network of stories that sought, unlike those of Jules Verne for example, to “throw science into the unknown”. However, this genre in the making existed before his manifesto, in novels that evoked space travel, utopian or abominable futures, lost civilizations, mad scientists or crazy inventions.

In october 1909, the magazine Le Spectateur published an article called « Du roman merveilleux-scientifique et de son action sur l’intelligence du progrès ». Its author, who was then still a young dilettante, Maurice Renard, had already published Fantômes et fantoches [Phantoms and puppets] and the more noteworthy Le Docteur Lerne, sous Dieu [Doctor Lerne, Sub-god]. In it, he explained that there was a literary genre that nobody suspected even existed, characterized by the representation of inventions that transformed the world and our relationship to it. Not the depiction of technological developments that were “almost” already achieved, the way Jules Verne did, but developments that were completely at odds with reality. “It was about throwing science into the unknown, and not imagining that it had finally accomplished this or that feat that was already being developed at the time.” This new literary category “uncovered for us the incommensurable space to explore, outwith our immediate comfort zone […] and transported us to other points of view, outside of ourselves.” He suggested naming this new branch of literature “Merveilleux-scientifique”, inspired by the English term “Scientific Romance”, because Renard was an admirer of H.G. Wells. He also quoted a number of authors that had already made this conceptual leap, such as the French authors Camille Flammarion, Edmond About, Charles Derennes or Villiers de L’Isle-Adam.

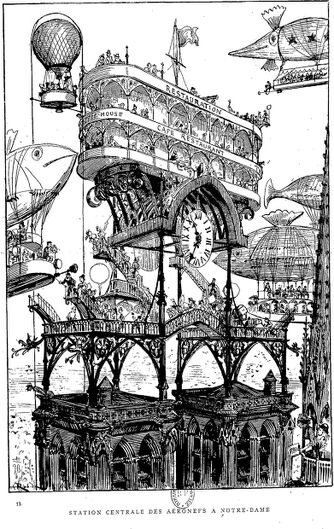

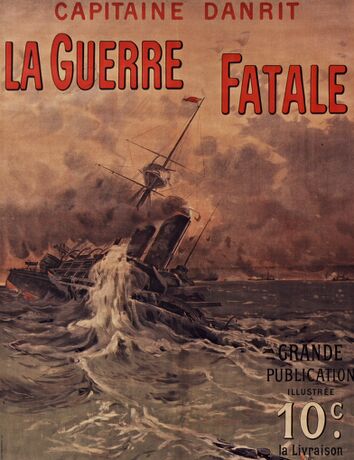

So, Renard was drawing on novels that had already been written. And if they are in fact not in the majority among French literary texts, there were nevertheless enough in the previous 50 years, that he could rely on them. First, there were writers in the continuity of Jules Verne, even if Maurice Renard mistrusted them, such as Albert Robida, who was a renowned cartoonist who illustrated his stories himself, namely the three most famous ones : Le Vingtième siècle [The twentieth century](1883), La Guerre au XXe siècle [War in the twentieth century](1887) and La Vie électrique [Electric Life](1892). His satirical stories took place in the short term future, and the numerous discoveries that he presented were not extravagant for the times. Paul d’Ivoi can also be cited here. His 21 volumes of Voyages excentriques [Eccentric Voyages](1894-1914) seriously resemble Verne’s Voyages extraordinaires [Extraordinary Voyages], with extra exorbitant innovations such as artificial clouds that sowed death, climate manipulators or even lasers. And let us not forget war anticipations, usually xenophobic and always nationalistic. The most well-known author of this type was captain Danrit, who described future conflicts where France was at war against most of the peoples of the world: the Germans in La Guerre de demain [The war of tomorrow](1889-1896), Africans in L’Invasion noire [The Black invasion](1895-1896), the English in La Guerre fatale [The fatal war](1901-1902) or Asians in L’Invasion jaune [The Yellow invasion] (1905-1906), with rather creative inventions in the art of destruction. These depictions of battles had quite a lot of success at the time, even though they are rather unreadable nowadays.

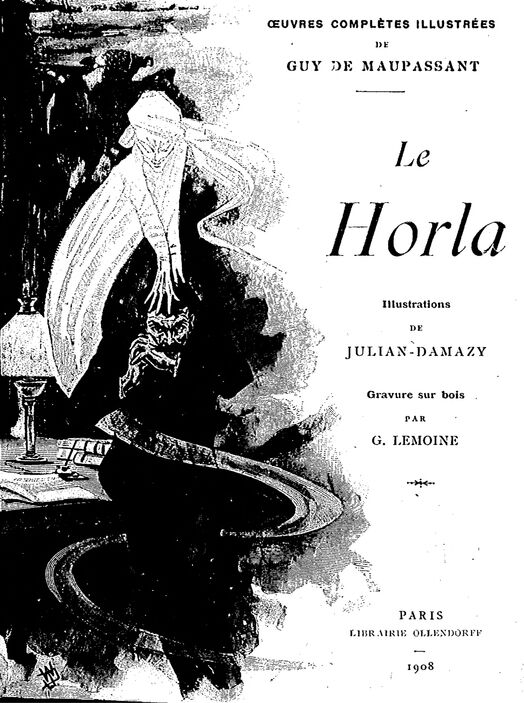

Other authors went further still, and anticipated the disruption advocated by Renard. The theme of “anticipation” as it was called at the time, became, as early as the 1850s, as a theme like any other, even though it was undervalued by those who held fast to the French tradition, where the style counted more than the idea. However, only few known writers attempted grappling with this genre, to say the least. Guy de Maupassant, in his famous short story le Horla [the Horla] told of the torments of the main character being overtaken by a creature that could be imagined to be from space. The same theme appeared in 1903, with the author John-Antoine Nau who put forward an individual overtaken by an extraterrestrial being in Force ennemie [Enemy force]. This story even received the first ever Goncourt prize; it was the only literary prize to reward a story of this type. And as to Charles Cros, his Un drame interastral [An interstellar drama](1872) jeeringly told of the love story between a Human man and a woman from Venus. In 1854, we have a truly cosmic transplantation with Charles-Ischir Defontenay and his Star ou Psi de Cassiopée [Star (Psi Cassiopeia)] which told, in a poetic manner, of the history of a civilization that lived on a faraway planet: it was perhaps the first “odyssey in space”.

Sometimes, interrogations that were almost metaphysical blended in with real science: Camille Flammarion , a very reputable astronomer of the time, and great popularizer of his discipline (see L'Astronomie populaire, [Popular astronomy] in 1880) embarked on writing stories that happened in space and that were almost philosophical, be it in Récits de l’infini [Stories of infinity] (1872), Rêves étoilés [History of a Comet], Uranie [Urania] (1889) or Stella [Stella] (1897).

But the cosmos wasn’t the only thing to attract writers: they were also tempted to write about the future. It could be a dark future, such as that depicted by Emile Souvestre, in 1846, in Le monde tel qu’il sera [The world as it shall be]which painted a world in which hope had gone, drowned in technicist ideology. On the other hand, utopias traced by revolutionaries were also to be found. For example, Le monde nouveau[The new world] (1888), an anarchist society depicted by Louise Michel. But the most important text of that period appears to have been L’Ève future [The future Eve] by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. In 1886, Villiers told the story of an android (he invented the word “andréide”) who was to replace a very beautiful but very dim woman. Beyond a certain misogyny, this book dealt with the question of truth and falsehood, real and illusionary, all whilst anchoring the subject in reality: the scientist is a real inventor, Thomas Edison, and the description of this android is rather technical. And of course, we must not forget the author Rosny aîné, who hadn’t yet contributed his major works in the area of anticipation (La Mort de la terre [The death of the Earth] in 1910 and Les Navigateurs de l’infini [Navigators of Infinity] in 1925) but had already written a fundamental text: Les Xipéhuz in 1887, which saw for the first time a battle to the death between prehistoric humans and a completely alien life form, where the absence of communication is staggering.

But this breakthrough into the unknown that Renard was looking for was more often than not the doing of popular authors, who were mostly interested in the limitless adventures of heroes that were simple, and easily grasped by all. Sometimes the stories were also to do with possible discoveries, or even various pipe dreams that came of humans’ alarming desires. They were first and foremost trying to captivate their readers. In fact, unlike in more recent times, the authors of stories in installments weren’t confined to precise themes, but rather covered all the themes that sold well. And amongst these, anticipation fiction came far behind love stories, exoticism, historical novels or detective stories, although it was beginning to become successful.

There were numerous trips into space (within the solar system). Les Exilés de la Terre : Selené-Company limited [The Conquest of the Moon: A Story of the Bayouda] by André Laurie told of Earthlings who tried to attract the moon closer to the Earth. Les Aventures extraordinaires d’un savant russe [The extraordinary adventures of a Russian scientist across the solar system] by Georges Le Faure and Henry de Graffigny (1888-1896) minutely described an exploration of the solar system in four volumes. La Roue fulgurante [The fiery wheel] by Jean de La Hire (1908) retraced the Martian abduction of Earthlings. Le Prisonnier de la planète Mars [Prisonner of the Vampires of planet Mars](1908) and the follow-up La Guerre des vampires [The War of the Vampires] (1909) by Gustave Le Rouge developed the ferocious struggle of a terrestrial hero against blood suckers that inhabited the red star. We could also mention other titles such as Un monde inconnu, deux ans sur la lune [An unknown world, two years on the Moon](Pierre de Sélenne, 1896), Les Terriens dans Vénus[Earthlings on Venus] (Sylvain Déglantine, 1907), Un Habitant de la planète Mars [An inhabitant of the planet Mars](1865, Henri de Parville) or Voyage dans la planète Vénus [Voyage to the planet Venus](Charles Guyon, 1889).

The success of interplanetary travel didn’t undermine writing about the future: thus we were treated to L’an 330 de la République [The Year 330 of the Republic]by Maurice Spronck in 1894 (the first time a utopia used a different calendar from ours), and Ignis by Didier de Chousy (in 1883 he saw a future filled with automobiles, moving walkways or geothermal energy). Other utopias, such as Ce que seront les hommes de l’an 3000 [What Men will be like in the year 3000] by Gustave Guitton, who imagined, in 1907, computers, synthetic food and controlled weather. Let us also mention La Babylone électrique [The electric Babylon] by Albret Bleunard (1888) and les Gratteurs de ciel [The scrapers of the sky] by Louis Boussenard (1907). Another theme, that then became preeminent, was that of mad scientists. Boussenard published in 1888 Les Secrets de Monsieur Synthèse [the secrets of Mister Synthesis], where he conceived a rich scientist who influenced the evolution of our species, with the following year 10.000 ans dans un bloc de glace [10 000 years in a block of ice]. André Couvreur described, with humour, a society governed by a megalomaniac doctor in Caresco, surhomme, ou le Voyage en Eucrasie [Caresco, superhuman, or travels in Eurcrasia] (1904) and a strange biological war in Paris in 1909, in Une invasion de macrobes [An invasion of macrobes]. Lost worlds were another leitmotiv : Les Profondeurs de Kyamo [The depths of Kyamo] by Rosny ainé (1896), Le Roi de l’inconnu[The King of the unknown] by Gaston de Wailly (en 1904, une terre creuse régi par un fou), Atlantis, by André Laurie en (les Atlantes perdus) and Le Peuple du pôle [The People of the pole] by Charles Derennes, about intelligent saurians living under the arctic cap.

In total there were several dozen novels, mostly published towards the end of the 19th century and shortly before the publication of Renard’s article. What later became “merveilleux-scientifique” was really budding at the time. Later, the publication of these types of stories increased greatly: Renard, Rosny, Couvreur, Béliard, Quirielle, and many others, who have mostly been forgotten in the present day. But space travel remained confined to the solar system, scientific progress was presented more like a danger to society than an improvement, and there was a proliferation of mad scientists. If many of these texts remain pleasant to read, they no longer evolve. And little by little, there are fewer and fewer of them. Rosny didn’t really write any more after 1925 and even Maurice Renard started writing stories that sold more easily so he could feed himself. He later wrote:

“To make a living by addressing intelligence, that, yes, really would be fantastic.”

After the Second World War, it was under the patronage of anglo-saxon themes that “merveilleux-scientifique” witnessed a rebirth in France, under the English term of science-fiction. It wasn’t until the end of the twentieth century that this forgotten part of our heritage was rediscovered. But Renard’s text of 1909 remains an important marker in literary theory and a testimony to this legacy of the 19th century.

Further reading

- Fleur Hopkins, Merveilleux-scientifique: a literary Atlantis and other blog posts in the « Merveilleux-scientifique » Cycle

- Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française was a free exhibition that took place at the François-Mitterrand site of the national library from 23rd April to 25th August 2019, during the opening hours of the library

- to read studies and “merveilleux-scientifique” stories available in the Gallica collections - or available to access in our reading rooms - here is a treasure map in the form of an online bibliography.

- and to explore the wealth of visual art and iconography of the movement, an Instagram account.

Ajouter un commentaire