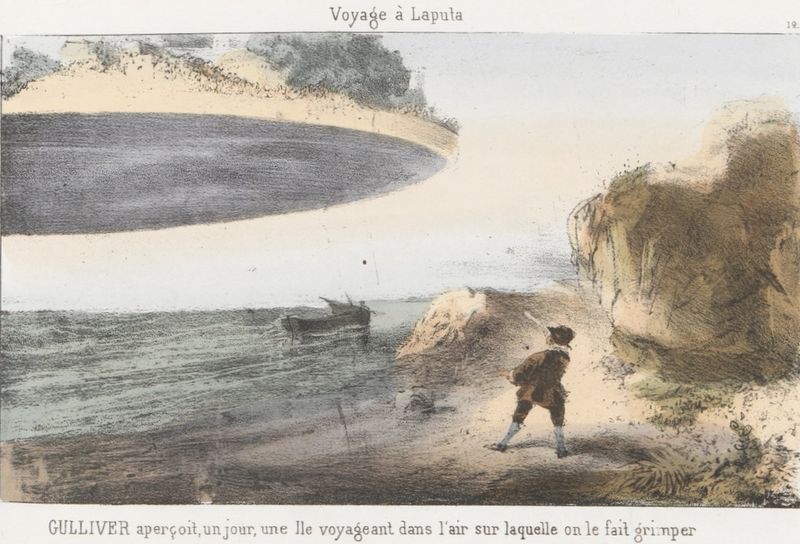

Jonathan Swift, Voyages de Gulliver [Gulliver's travels], drawings by E. Morin, Paris : A. de Vresse, p. 12.

Asking themselves about the place of Man in the universe and what we know of it, these works remain steeped in the irrational, and foreshadow the French proto-science-fiction, the “merveilleux-scientifique”.

Utopias and discoveries

In speculative fiction, science-fiction neighboured fantasy and marvel right from the invention of the novel in Great Britain, particularly in travel writing which enabled the account of discoveries and improbable encounters. Readers discovered Sir Thomas More’s utopia, published in 1515 , and the ideal city imagined by Sir Francis Bacon in New Atlantis (1626). These forms of literature could be considered as the ancestors of science-fiction, in the sense that they were about imaginary travels that lent themselves to the staging of inventions and bold experiments, as could be found in the volumes entitled “Cabinet des fées ” published by Charles Garnier between 1781 and 1798, which brought together “travels, visions and cabalistic novels”. In this collection were published Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, Micromégas ou voyages des habitants de l’étoile Sirius by Voltaire or Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe.

In literature, the supernatural was clad in ancient forms, particularly on the other side of the Channel, at the end of the 18

th Century in Gothic novels, such as

The Castle of Ortranto by

Horace Walpole (1765) and

The Castles of Ahtlyn and Dunbayn by

Ann Radcliffe (1789), which plunged the heroines and heroes at the heart of obscure mysteries. In those works, readers found walking headless bodies, curtains that moved with no apparent reason and the strange glow of the full moon. All these ingredients of the Gothic novel aimed not only to frighten the readers but also offered an aesthetic of terror, far from the rational laws of nature. As early as 1818,

Mary Shelley pushed the limits of reason by imagining Frankenstein, a monstrous creature. At the beginning of the novel, the main protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, gives up his research in alchemy, after converting to real science, and wants to create his Masterpiece: a monstrous being, in the hope of making him come alive again by injecting a vital spark. We can see in

Frankenstein the first novel that developed the state of mind “fictive pre-science” according to modern preoccupations, as it opened up the debate on science and the theme of the sorcerer’s apprentice. Inspired by her conversations with

Byron,

Shelley and the works of

Erasmus Darwin, namely his works

Zoonomia and

The Temple of Nature, which lead up to the theory of evolution, Mary Shelley explored the result of a scientific experiment, and thus took part in the creation of an archetype of science-fiction. From then on, we can talk about “scientific romance”, which saw the light of day between 1818 and 1895, echoing the industrial revolution in Great Britain.

« Scientific romances »

During the 19

th Century, English society witnessed the birth of the idea of fictive literature among writers, to introduce the readership to technological enlightenment. Torn between the desire of progress and the denunciation of its potential perversions, writers speculated, explored, dreamed or had nightmares about the new world in the age of the machine. When

The time machine by

H.G. Wells was published in 1894 and 1895, travel to the future was explained by recourse to a contemporary scientific hypothesis. To project themselves into the future, the time traveller used a machine, of which Wells justified the existence by leaning on speculation at the time around the fourth dimension in space. He then imagined humanity to be subdivided into two species, the Eloi and the Morlocks, resulting from differential evolution and foreshadowing the possibilities of biological manipulations. But we are here well and truly in the presence of a novel, the account of an adventure, in the sense of

scientific romance, aiming to be accessible to the general public. In the same way as in

The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, innovations were described, and made important scientific hypotheses more tangible with a story that staged a confrontation between humanity and hostile extra-terrestrial race. Wells questioned the social implications as well as the objects of science and their effects. Similarly,

Arthur Conan Doyle, beyond the adventures of the famous detective Sherlock Holmes, wrote

wonderful fable-like adventure stories or pseudo-historical stories about rediscovering the underwater city of Atlantis, or the survival of tribes in the highlands of the Amazon at the beginning of the quaternary era. Then, it was not until the transition to a rational literature of scientific imagination at the beginning of the 20

th Century that inventions and industrial and social transformations no longer opposed arts and science, but linked them more intricately.

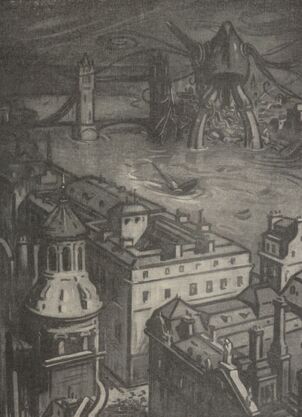

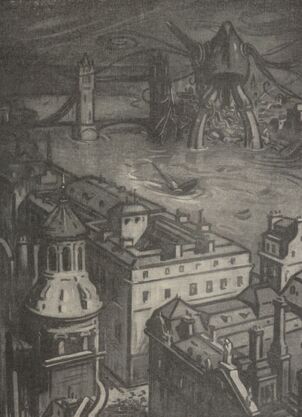

H. G. Wells, La guerre des mondes [The war of the worlds], ill. de M. Dudouyt. Paris :Calmann-Lévy, 1917, p. 72.

H. G. Wells, La guerre des mondes [The war of the worlds], ill. de M. Dudouyt. Paris :Calmann-Lévy, 1917, p. 72.

Science and strangeness

More ambivalently, writers overseas discussed science to question our own relationship with reality and put into narration nightmares, visions and supernatural phenomena, such as

Edgar Allan Poe, who imposed himself as the master of the genre with short stories and fairy tales where anguish, the supernatural, fear, and strangeness, all mingle. While continuing in the tradition of the English Gothic, he described paranormal phenomena such as the red moon in

The fall of the house of Usher. Is it due to a climatic occurrence linked to an actual red moon, or is it in fact stained with the blood of Madeline, who was entombed?

Dix contes d'Edgar Poe [Ten tales by Edgard Poe], translated by Charles Baudelaire

and illustrated with 95 original compositions by Martin Van Maële carved on wood by Eugène Dété. Paris, 1912, p. 61.

Other mysterious phenomena appeared in novels by

Henry James, where ghosts could only be seen by children, as in

The Turn of the Screw. Having a passion for science, James tried to communicate with his deceased brother, and questioned the perception of reality and consciousness in his writing. Other writers took an interest in these phenomena at the end of the 19

th Century, such as

Oscar Wilde, who indulged in staging the supernatural in

The picture of Dorian Gray (1891). The portrait takes on the traces of the passage of time of he who does not age. This fin-de-siècle period was, let us be reminded, a particular moment where writers integrated recent discoveries in medicine and the theories of the unconscious, playing at staging a scattered subject, who is fragmenting or splitting in two, plagued by hauntings and nightmares in a changing society.

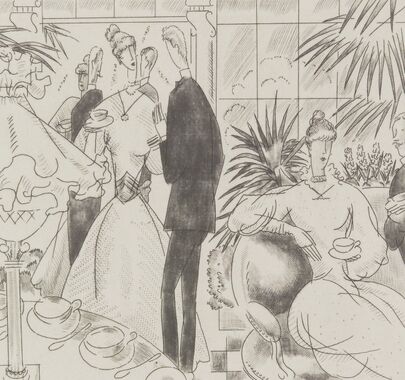

Jean-Émile Laboureur, Illustration for the Portrait de Dorian Gray [The picture of Dorian Gray], print, scene of a social reception, 1928

Further reading:

Translated from French by Claire Carolan

Ajouter un commentaire