Born in 1752 in Norfolk, in a family that belonged to the English gentry, Frances Burney, often referred to by her nickname “Fanny”, grew up in an environment that was conducive to reading, amongst her five siblings. Upon the death of her mother when she was 10 years old, she felt a compelling need to invent stories and she began to write, despite this activity not being perceived as proper for a young lady in polite society at the time.

E. Lassaugue, « Gens de cour en exil », Revue de l'histoire de Versailles et de Seine-et-Oise, Paris : H. Champion, 1905, p. 11

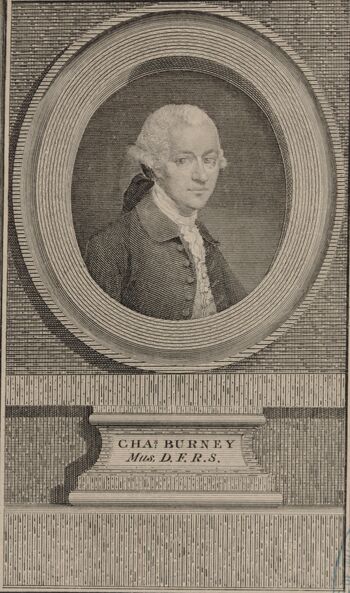

When her father remarried in 1767, the family grew bigger. Frances’s step-mother, Elizabeth Allen, upon discovering the manuscript of Frances’s first novel, forced her to burn part of her literary production out of fear that her father, Dr Charles Burney, renowned musicologist, would condemn her creative works - which he had not known about until then. From then on, Frances Burney had to publish her works anonymously.

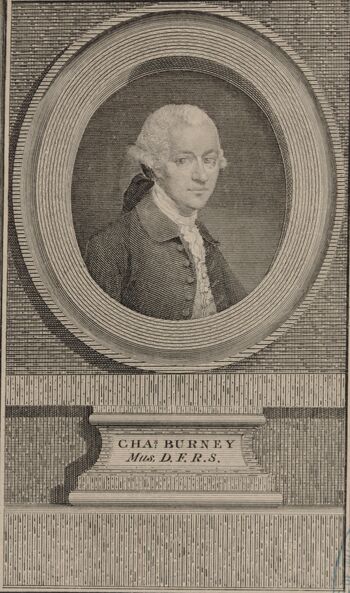

Portrait of Charles Burney, Londres : J. Sewell, 1785

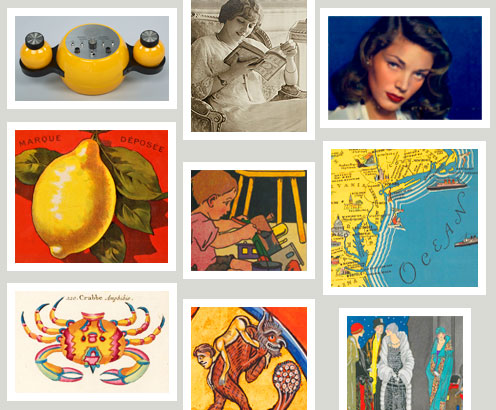

Employed as a lady companion to Queen Charlotte between 1786 and 1791, which was a social position that her family favoured to that of a writer, Fanny Burney had little time to devote to writing, but she nevertheless kept a journal, and even managed to write novels before she married General Alexandre D’Arbley in 1793, who encouraged her to pursue her writing activities.

Portrait of Alexander D’Arbley © Burney Center, McGill University

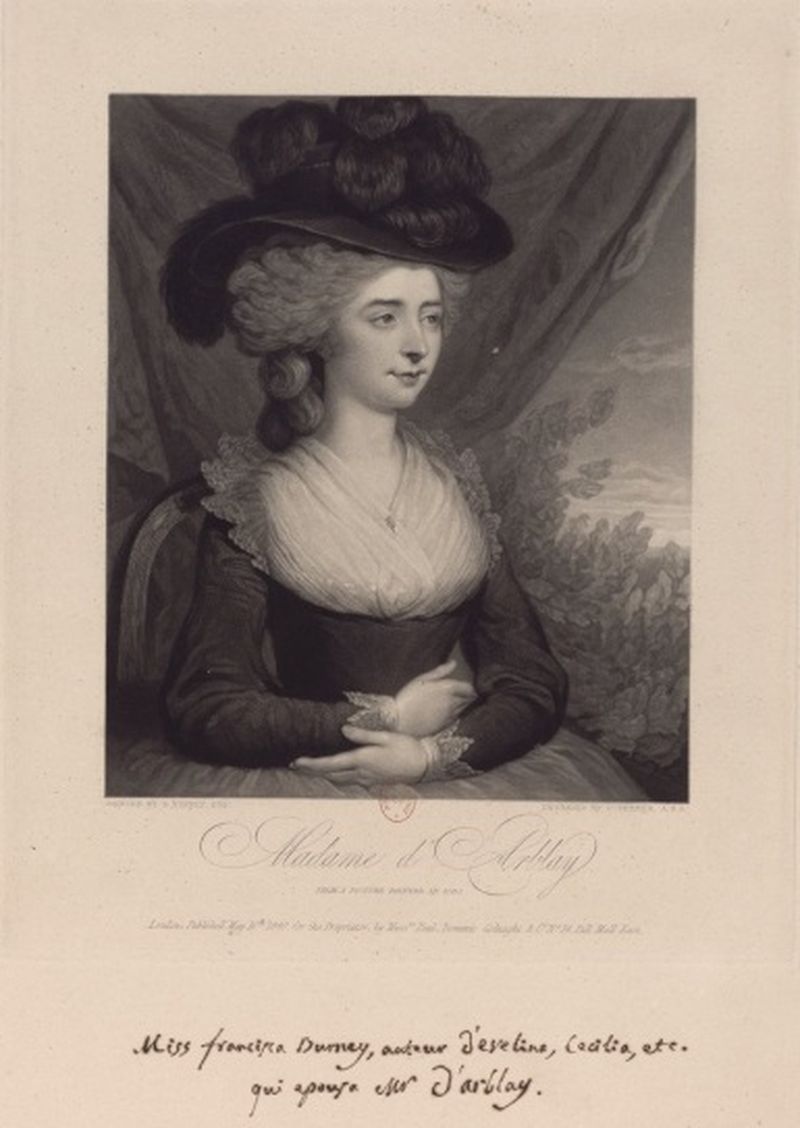

Her first novel Evelina or the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (1778) brought her immediate success. In this fictional account which mimics the style of an autobiography, Frances wove the tale of a journey of initiation. Its originality resided in a subtle balance between a bildungsroman and a personal diary. By adopting the genre of the epistolary novel, the author followed in the steps of the lineage of women writers inaugurated by Aphra Behn, who published an epistolary novel Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1648-1687) and published the imaginary story of an African prince in Oronoko in 1779.

Portrait of Aphra Behn © Wikimedia

There were a few other women writers, such as Sarah Fielding and Elizabeth Griffith whose originality dominated the literary market in the 1770s. But Burney was one of the first to denounce the prejudice towards the female sex and the literary genre of the novel, at a time when women were supposed to aspire only to a quiet domestic and personal life. Being a writer was even more difficult for women in a patriarchal society that imposed a feminine ideal of an angelic and silent woman. The instant success and popularity of her novel Evelina launched her career and contributed to consolidate the emergence of the novel towards the end of the 18th century, paving the ground for novelists such as Ann Radcliffe or Jane Austen.

Evelina, or A young lady's entrance into the world, manuscript [before 1778] © The Morgan Library

Evelina is about an innocent young girl who is confronted with the world and its violence through a perilous journey, where she seeks autonomy and independence. In her personal diary, she confesses her feelings and shares the quality of her observations on the society she meets during balls and at evening parties, lamenting the vanity of some (the Branghton sisters) or the futility of others (Mme Duval). Burney admired Jonathan Swift and Samuel Johnson, whom she considered to be literary models, and she followed their steps in the traditional novel whilst bringing a feminine consciousness to her work. She wrote other novels that staged the destinies of young heroines: Evelina, Cecilia and Juliet, who enabled her to put into practice the ideas of female autonomy that were formulated several years later by Mary Wollstonecraft in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). At that time, women had to appear innocent, unknowledgeable and not show their intelligence too much:

L. Etienne, Revue contemporaine, Paris, 1858, p. 282

Often considered as sensual, non-rational beings, they were undervalued. Burney’s novels emphasise the poor education of women, which gives them an inferior place to men. It is in the way she portrays her characters that she shows the importance of developing thinking skills and moral principles in young ladies, rather than teaching them talents intended to make them attractive to their future husbands. In the following novels (Cecilia, published in 1782, and Camilla, 1796), both very popular, the characters appeal to the readership, who appreciate the ironic tone and the rich descriptions of London society:

Cecilia, ou Mémoires d'une héritière. Londres : Paris, 1784, p. 36

The development of culture and sensitivity which were already present in sentimental novels then appears in the first Gothic novels. Several scenes in Camilla resemble frightening dreams where the heroine is terrified by irruptions. Similarly in The Wanderer (1814), a scene of nocturnal wandering in the forest suddenly turns surreal and terrifying, and foreshadows gothic stories like The Mysteries of Udolfo (1794) by Ann Radcliffe. Frances Burney also incorporates references to the sublime, defined in 1765 by the philosopher Edmund Burke through frightening and mysterious descriptions.

Edouard Dietrich, Bataille de Waterloo, Lith. von Roland Weibezahl. Erfurt : Muller'schen Buchhandlung, 1815

Residing in France between 1802 and 1815, Frances Burney met the painter Jacques-Louis David and his wife. She also met Napoleon Bonaparte, and described this complex historical period in her personal diary, including the Battle of Waterloo. At the height of her career, she was introduced to London literary circles by Samuel Johnson. There she met writers, philosophers and thinkers:

A. Boviès, La Nouvelle revue, Paris : juillet 1911, p. 291

Following the well informed advice of the literary circle, she wrote for the theatre, published other novels and continued writing in her personal diary all her life, describing society and its changes with an ironic and innovative tone.

Further reading

You can consult the website dedicated to the archives of Fanny Burney and her family.

And read the previous blog posts in the series « English Women Writers »

Isabelle Le Pape

(translated from French by Claire Carolan)

Ajouter un commentaire