An English Lady in Turkey : Lady Montague

Lady Montague was the first female westerner to travel to Turkey. She left behind a set of correspondence which depicts a country very little known of Europeans at the time. Her letters, written during her travels to Europe, Asia and Africa were published in 1763 and inspired writers such as Chateaubriand and Lord Byron.

A life of adventures

Eldest daughter of the Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull and Lady Mary Feilding, Mary Wortley Montague was born in 1689 and grew up amidst the London intelligentsia, she rubbed shoulders with Sir Richard Steel and Joseph Addison, and she studied Latin. In 1712 she married Sir Edward Wortley-Montague, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, with whom she elopes following her father’s opposition to the union. She followed her husband during his missions to Rotterdam, Vienna, Istanbul, Greece and North Africa.

.

Women traveling to the East

The first women who travelled during the 18th century were mostly English women, often aristocrats, or at least rich and independent enough to venture out on the roads of Europe and the near-East which included the Balkans, Greece and Turkey.

As early as the 17th century, Lady Ann Fanshawe used to dress up as a sailor boy to fight pirates along the Spanish coasts, but it wasn’t until the start of the 19th century that women really began traveling the routes to the East, like Lady Stanhope, a rich British aristocrat, adventurer in the Near-East region, who was proclaimed “Queen of Palmyra” by the Bedouin tribes, also described by Lamartine in Voyage en Orient (1835).

Alphonse de Lamartine, Voyage en Orient, Tome 1. Paris, 1913-1914, p. 166

Vue du Serail du Grand Seigneur ou la Grande Sultane fait sa demeure ; pris du coté du Jardin a Constantinople. A Paris chez Basset rue St. Jacques [ca 1770]

It wasn’t until the 1840s that traveling for leisure became more widespread, and that female travellers gradually became a more common sight abroad. Thanks to travel writing, women had access to a public space which was traditionally reserved to men. Be it writing narratives of the Mediterranean Sea shores or those of the North Sea, or even of the Slavic world, female writers gained popularity by their accounts of relatively unknown regions, such as Norway for Mary Wollestoncraft or the Baltic region for Elizabeth Rigby. A mandatory stop during faraway travels, on their way back from Egypt, Turkey or Palestine, Greece was also a favoured travel destination for these women travellers. Such countries were occasionally the object of academic writing, but were mostly referred to in their phantasmagorical dimension. Thus, Constantinople sparked dreams at the mention of harems. Following the example of Lady Montague, other women travellers gazed at their surroundings with insatiable curiosity, always prepared to discover new environments, new cities and newly discovered ancient ruins, all whilst becoming aware of how fashion and morals were in fact relative to a culture. However, the itinerary of travel and discovery also included fear, hunger, cold and general discomfort caused by such travels. Nevertheless, Lady Montague was never discouraged, overcoming the plague, harsh winters and other hazards of this lifestyle.

The fabulous East, a reservoir of inspiration

The Montagues had a certain amount of assets. In 1717, despite being a rather marginal figure in the diplomatic landscape between Turkey and the West, Lady Montague gave the first ethnographic account of a civilisation that she was able to observe prior to the slow decline of the Ottoman Empire. Turkey was then open to knowledge from the West, especially in the areas of medicine and architecture... Seen both as rough and refined, near and far, Turks were the main protagonists of a world stuck between freedom and despotism. Lady Montague’s letters emphasized the setting. In the background lay the cities she travelled across: the citadel of Belgrade, the antique remains near Sofia, byzantine ruins, the crumbling Christian mosaics of Saint Sophia, the gracious minarets reaching all the way up to de mosque domes which rose akin to “cabinets and candlesticks” arranged in a disorderly fashion.

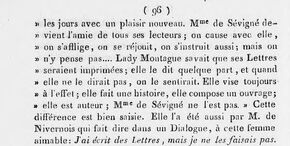

Revue Tablettes universelles, Paris, 1823, p. 365.

The Turkish Letters published in 1763 were reprinted many times. These travel accounts inspired many travellers in the 19th Century, writers, orientalist painters, namely Delacroix who travelled to the East, but also Ingres.

François-René de Chateaubriand, Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem et de Jérusalem à Paris, en allant par la Grèce et revenant par l'Egypte, la Barbarie et l'Espagne. Tome 3. Paris : Le Normant, 1811, p. 125.

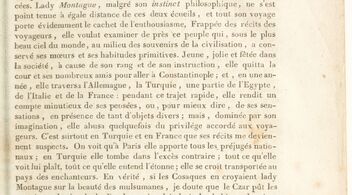

The Turkish bath according to Lady Montague.

Inspired by Lady Montague’s letters describing her visit to a public bath reserved to women in Istanbul towards the end of her life, Ingres created a painting of intense eroticism with a harem scene which associates nude bodies and the theme of the Orient, playfully creating an arabesque-dominated composition.

Journal pour tous : magazine hebdomadaire illustré, Paris : Ch. Lahure, 1855-04-07, p. 13.

Joseph Straszewicz ; Laure Junot Abrantès, Les femmes célèbres de tous les pays : leurs vies et leurs portraits, Paris : Lachevardière, 1834, p. 78.

In this tondo, we can see dozens of naked Turkish women, sat in different positions in an oriental indoor setting, arranged around a pool. Some swimmers are coming out of the water, stretching or dosing. Others are drinking coffee.

However, unlike Delacroix, Ingres never went to the East and dreamed up this scene based on what he had read. He was inspired by the Letters of an English ambassador in Turkey in the 18th Century written by Lady Montague, that include a letter in which she describes her visit to a women-only public bath.

Gérard de Nerval, Scènes de la vie orientale. Les Femmes du Caire, Paris : F. Sartorius, 1848, p. 349.

Further reading

To explore other travel accounts of the Near East, see the selection of documents suggested on the Bibliothèques d’Orient website.

Discover the exile in Italy of Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

And read the previous blog posts in the series « English Women Writers »

Translated from french by Claire Carolan.

Ajouter un commentaire