The novels of the Brontë sisters revolutionised the conventions of feminine writing in mid-19th Century England. Emily (1818 – 1848) took up writing with her sisters Charlotte (1816-1855) and Charlotte (1820-1849) in her teens, inspired by novels and many periodicals from the Haworth presbytery library, where they lived with their father, who was a vicar, and their aunt Elisabeth Branwell who came to live with them and bring them up after their mother died in 1821. Poems, plays and accounts of expeditions composed a wide range of written works they produced, mostly taking place in an imaginary Africa, which they gathered in the form of sagas in the kingdom of Gondal. This unique literary production was progressively made available to French readers, from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, with much confusion around the works and their authors. Their literary career was inaugurated with a collective anthology of poems self-published under their pen names: Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.

Published only a few months apart, Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë and Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë created a sensation with the background of their stories set in northern England, the staging of heightened passion and the new role granted to the heroines struggling to be recognised as equals to their fictional male counterparts. When it was initially published in 1847, Wuthering Heights caused a scandal, even though the public was immediately fascinated by the vitality and originality of Emily Brontë, hidden under her pen name Ellis Bell. Such a novel couldn’t be further away from the Victorian moral order, and it shocked the readership by its crude language and the unleashing of passions. In 1850, Charlotte Brontë attempted to reconcile the public with her sister’s work by writing a preface for it, in which she told of the discovery of Emily’s poems and described the simple life she lead in Yorkshire, which inspired the plotline of Wuthering Heights with its rustic lore and austere moorland landscapes:

Léo Quesnel, « Les femmes de lettres en Angleterre », La Nouvelle revue, 1881, p. 155

Until Charlotte’s revelation of the true identity of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, critics believed that Emily Brontë’s novel had been penned by a masculine author. The critics formulated the prejudices of their time against a novel which also shocked the literary critics when it was translated in France. Charlotte took it to heart to make the readers better understand the novel: “Is it good, is it commendable to create beings such as Heathcliff, I do know: I do not think so. But I do know this; that a writer who has a creative gift possesses something which they cannot entirely master – a force that, sometimes, has its own will and its own life.” The complexity and the violence of Wuthering Heights, translated into French as Les Hauts de Hurlevent, triggered reactions and unrest around a novel which obeyed the laws of no known genre, yet recalled the atmosphere of gothic works and supernatural tales:

B. Ernouf. « Le roman terrible en Angleterre », in Revue contemporaine, Paris, 1861, p. 171

Critics went as far as reproaching the author her immaturity, considering that it was a beginner’s novel, or even a written attempt by her sister Charlotte. It must be said that Emily did enjoy making light of her reader, weaving narratives within one another, from different points of view, that of Nelly, the servant, that of Lockwood, the traveller, or going back to childhood memory accounts of Catherine and Heathcliff. Moreover, by creating Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, the Brontë sisters claimed their right to play with identities, blurring the limits between fiction and reality, in order to preserve their peaceful lives. Each one of them dared to free herself from conventions by providing less idealised portraits of feminine characters than in novels of previous periods. Their heroines (Catherine Earnshaw of Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre and Helen Graham of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall) lead unprecedented struggles and forwarded demands in a world that was still very patriarchal:

B. Ernouf, « Le roman terrible en Angleterre », in Revue contemporaine, Paris, 1861, p. 172

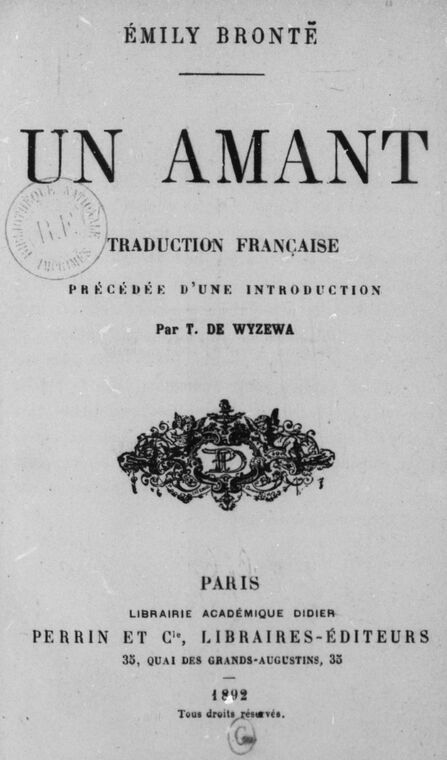

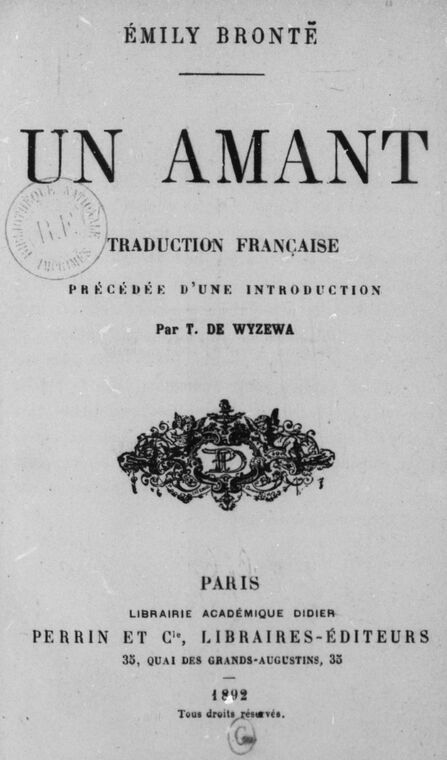

The editions of her works kept at the BnF (French National Library) constitute a body of rich study materials, with book covers, prefaces and illustrations that enlighten the modern researcher as to the way Emily Brontë was presented to her contemporary readers by her editors and translators in France. A discernible evolution progressively emerges, especially with regard to the quality of the translations which each offer many variations of the French title in the early 20th century, while trying to remain faithful to the dialects and terms typical of the region of Yorkshire. In parallel, theatrical and cinematographic adaptations all contributed to modify the perception of the novel by the beguiled public. So it is long after its publication across the Channel that French readers became aware of the particular role played by Emily Brontë in the history of the British novel. Among the translations of the original editions kept in the Literature and Arts Department of the BnF, there are many reprints, publications of illustrated versions of the novel and other versions intended for a younger audience. The oldest edition kept by the library is dated 1873, and includes both Wuthering Heights, and Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey (London : Smith, Elder and Co), while the first French translation by Théodore de Wyzewa dates back to 1892 (Un amant, Paris : Perrin) :

Emily Brontë, Un amant, traduction française par Théodore de Wyzewa, Paris : Perrin, 1892

The French title varied with each new translation : : Les Hauts de Hurle-vent (translated by Frédéric Delebecque, Paris : Payot éditeur, 1929), Les Hauts des Quatre-Vents (translated by M. Drover, Paris : Albin Michel, 1934), Haute-Plainte (translated by Jacques and Yolande de Lacretelle, Paris : Gallimard, 1937), La maison des vents maudits (translated by Elisabeth Bonville, Paris : Gründ, 1942) or even Heurtebise (translated by Martine Monod and Nicole Soupault, Paris : Union bibliophile de France, 1947). These different editions offer a number of variations which reflect the appropriation and even sometimes deformation brought by the translators, who adapted a complex novel that contained crude language. So we had to wait until 1892 for the first translation, and then important French publishers such as Payot, Albin Michel or Gallimard adopted the novel, appealing to a wide audience. Finally, numerous paperback editions flourished. Nevertheless, as early as 1855, francophone literary journals enabled readers to discover the works of this English writer, with reports and biographical information in periodical publications such as L'Athenæum français, the Revue contemporaine, La Nouvelle revue or L’Année littéraire. In these journals, critics recounted the debates that were all the rage in England around the publication of the novel or simply stuck to describing the everyday life of this unknown young woman who lived as a recluse in a rough region:

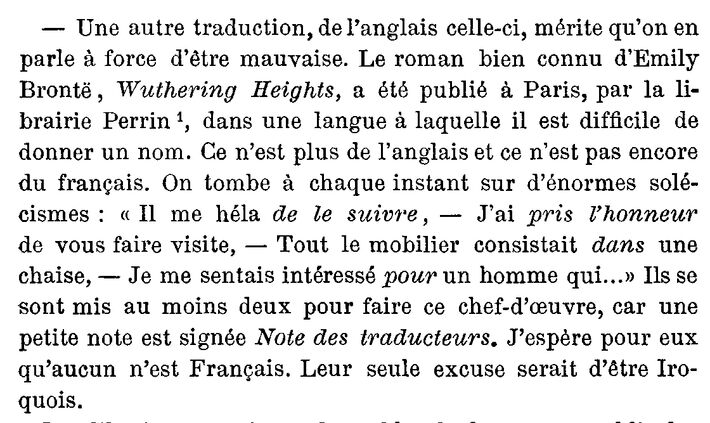

Bibliothèque universelle et Revue suisse, 1892, p. 167

B. Ernouf, « Le roman terrible en Angleterre », in Revue contemporaine, Paris, 1861, p. 153

Other than the monographs, numerous theatrical and cinematographic adaptations enabled the appropriation of this crude and at times misunderstood novel by the public. In 1938 the novel was adapted for the theatre by Mr Vanderic, under the title Les Mauvais anges : pièce en trois actes et cinq tableaux, with a scenario by Maurice Rostand, and again in 1979 in a show by Robert Hossein called Les hauts de Hurlevent. And finally, in 1982 the audience was able to discover a choreographic adaptation by Roland Petit.

Les hauts de hurlevent, ballet sur une chorégraphie de Roland Petit, Paris : Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 26-12-1982, photographies de Daniel Cande (All rights reserved), musique de Marcel Landowski

But the most famous adaptation remains that of American film director William Wyler with Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier in the main roles of Les hauts de Hurlevent in 1939. The Spanish film director Luis Buñuel also made a more experimental version in 1954 under the title Abismos de pasion. In 1970, a more popular version was shot by Robert Fuest, with Anna Calder-Marshall and Timothy Dalton in Les Hauts de Hurlevent. As to the British film maker Peter Kosminsky’s adaptation, it is closer to a dramatization with Juliette Binoche and Ralf Fiennes in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1992). Beyond legend and myth, and beyond the worship of the Brontë sisters, what should be remembered is the way they contributed to the revolution of the English novel and to the staging of passions in the mid-19th century.

Merle Oberon, recueil Les hauts de Hurlevent, film de William Wyler d'après Emily Brontë, 1939

Further reading

Discover the heritage of the Brontë sisters on the website of the Brontë Society

Leaf through the manuscripts of Emily Brontë

Immerse yourself in the world of the Brontë sisters

And read the previous blog posts in the series « English Women Writers »

Isabelle Le Pape

(translated from French by Claire Carolan)

Ajouter un commentaire