Gallica

de la BnF et de ses partenaires

Jules Verne : the extraordinary rather than the marvellous

Maurice Renard, theoretician of the « merveilleux-scientifique » always refuted any form of association with Jules Verne. This openly-declared literary feud was nevertheless not synonymous with disavowing the work of Verne, which was “deserving of science”, and offers us the opportunity to briefly revisit the life and works of the author of the Voyages Extraordinaires [Extraordinary voyages] series.

Jules Verne by the Nadar Wokshop

« [Jules Verne] is a writer, no matter what anyone says ». Maurice Renard

As proof that Verne’s work still provides fertile creative ground today, one need only mention the names of Phileas Fogg, or Captain Nemo and his famous Nautilus, or even to consider the success of the recent adaptation by Christian Hecq (stage director at the Comédie Française) and Valérie Lesort (stage director at the Opéra-comique) of Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers [Twenty thousand leagues under the sea] at the Comédie Française theatre. Although if there are numerous modern adaptations, let us be reminded that, one month away from the fiftieth anniversary of the first step on the Moon, Jules Verne had imagined, one hundred and five years before it occurred, a trip to Earth’s natural satellite (De la Terre à la Lune, trajet direct en 97h 20 minutes [From Earth to the Moon, direct journey in 97 hours and 20 minutes]) with enough creative force that one of the first great films of the history of cinema was directly inspired by it, under the facetious directorship of Georges Méliès.

Hetzel, the « sublime father » (Marcel Moré)

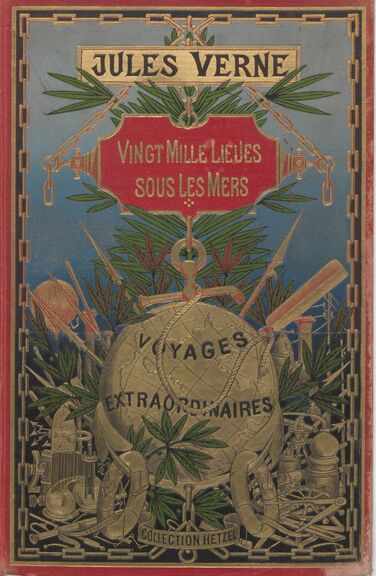

This collection of illustrated hardbacks, where science is always in the background, and often even the main subject or protagonist, and absolutely inseparable from Jules Verne for any reader of the 19th century, would never have seen the light of day without the intervention of a visionary publisher: Pierre-Jules Hetzel.

Robur-le-conquérant [Robur the Conqueror], by Jules Verne, Hetzel Collection (Paris), 1904

It was in 1862 that Jules Verne finally saw one of his manuscripts accepted: it was what was to become Cinq semaines en ballon [A voyage in a balloon], a reworked version of a text entitled “un voyage en l’air” [journey in the air], in which Verne, following Hetzel’s advice, emphasized the scientific side of the adventure. It was during this collaboration with the publisher that Verne managed to refine his literary goals, and put in place what would become the distinctive characteristics of his works, thus summed up by Maurice Renard in the journal L’intransigeant of January 6th, 1928 : “the work of Jules Verne is an admirable series of familiar lessons, written with the intent of entertaining while learning.” And indeed for a long time, critics refused to see anything else in Jules Verne’s work than the will to teach the basics of science in the form of adventure stories, creating an imaginary world in which to spread knowledge, a way to share science perhaps, more than popularize it. It was about introducing readers to and making them like this science which seemed to be able to explain everything and accomplish everything in this second half of the 19th century and which went beyond the possibilities of the imagination in the real world.

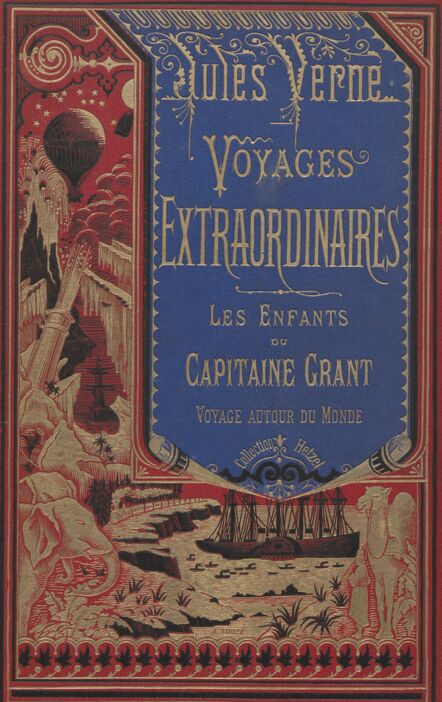

But Hetzel did more than just give Verne writing guidelines and generic advice: he also implemented for him the principle of a series, which enabled Verne to produce new works regularly, and that went hand in hand with the birth of Children’s literature, which had been marginal or didn’t belong to specific collections until then. In this context, Hetzel provided a very precise visual identity for Verne’s stories. Today still, they can be easily identified at first sight thanks to the attractive presentation of the collection. The particular reason for these being published as hardbacks, was that books for children were then luxury goods, which supposed extra spending on the part of the family, however the books had to remain affordable, which only became possible in the 1870s thanks to new publishing techniques. This was also the birth of “gift books”, which explains the red and gold covers with their beautiful engravings: books acquired a strong symbolic value as beacons of the child’s education in the family library, and so the illustration built up allegorical capital.

In this way, whereas the covers of the first editions of the Voyages extraordinaires [Extraordinary voyages] series were quite independent of the content – for example, floral motives for Voyage au centre de la Terre [Journey to the centre of the Earth] – the subsequent covers were illustrated by a picture that synthesized the story, when Jules Verne became famous. The picture wouldn’t necessarily reflect the themes of the novel itself, but would allude to the “Vernian reading pact” which was clear in the reader’s mind: scientific objects, means of transport, places, weapons… It was a real visual identity that was created by Hetzel’s editions of the works of Jules Verne.

The dreamlike aspect: the extraordinary and science at the service of the imagination

The goal was admittedly to write the « science novel », but also thereby to give birth to a new form of wonderment: that which came from this science. In the end it was about “replacing the wonder of fairies by another, the wonder of a thinking and knowledgeable humanity” (Marc Soriano). While Maurice Renard wanted to give fairy tales a kick-start with the merveilleux-scientifique novel – where one of the names he gave to his genre came from: “the fairy tale with a scholarly structure” , Jules Verne on the other hand turned to science that was more surprising and “extraordinary” than everyday life or an absolute invention.

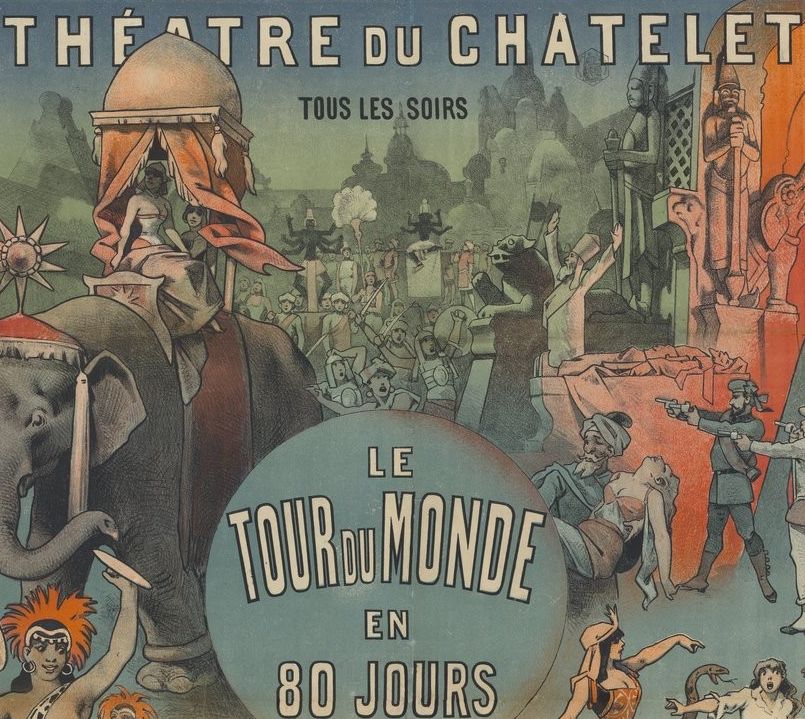

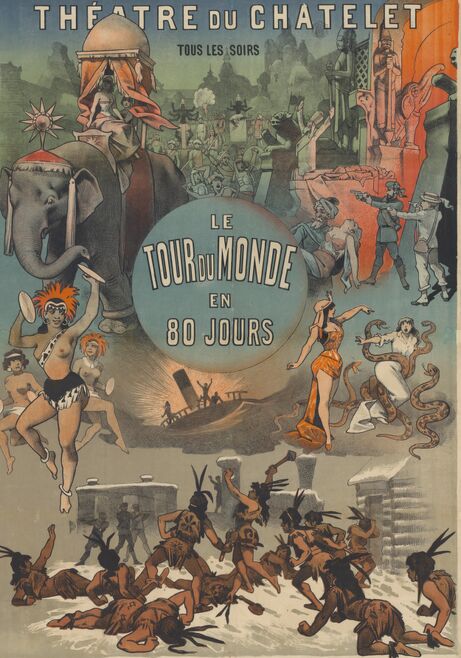

This science that was an anchor point for Jules Verne’s novels didn’t enclose its stories in a narrow frame that was perfectly realistic, but on the contrary gave the author a shrine in which to develop his imagination via the characters brushed by his pen, about to become, in the eyes of his readers, real “types” (think of the misanthropic genius Captain Nemo). Moreover, where Maurice Renard was the incarnation of the “motionless travel” (title of one of his works of 1908), placing the marvellous in the here and now, the work of Verne is, for its part, an incarnation of mobile travel, operating thanks to science and verticality (De la Terre à la Lune [From Earth to the Moon], Voyage au centre de la Terre[Voyage to the centre of the Earth] , Cinq semaines en ballon [Five weeks in a balloon ]…), and horizontality (Le Tour du monde en 80 jours [Around the world in 80 days], les Enfants du Capitaine Grant [Captain Grant’s children]), in a real but unknown elsewhere (Vingt Mille lieues sous les Mers [Twenty thousand leagues under the sea]), in an imaginary elsewhere (L’Île mystérieuse [The mysterious island]), and even in time, by the prospective aspect of his work.

Although Jules Verne wrote as a connoisseur of scientific advances and theories, the anticipatory aspect of his work should not be forgotten: not content with describing progress, he sometimes preceded it. Thus, in Le Château des Carpathes[The Carpathian Castle ], a love story – of cursed love – much more than a scientific novel, where the power of imagination is at work, and where Verne wrote on the first page: “if our story is unlikely today, it could be likely tomorrow, thanks to the scientific resources that belong to the future”. And indeed, in this truly gothic novel, he foresees a type of video projector or hologram projector, which enables the romantic Count Rodolf de Gortz to revive the image and voice of the opera singer he used to love.

Illustration par Léon Bennett pour Le Château des Carpathes (1892)

Maurice Renard readily admitted this gift Jules Verne had for anticipation, combined with a fine understanding of scientific mechanisms : “he would only be a brilliant teacher (and that is already a lot!), but for the occasional flash of a hypothesis that manifests itself in him”! Both men shared a love of logic: Renard’s merveilleux-scientifique consisted in altering a physical, chemical or biological law, but then what followed was perfectly logical and rational (unlike what had driven marvellous travel writing until then, such as in Histoire comique des Etats et Empires de la Lune [Comic history of the States and Empires of the Moon] in the 17th century for example.)

Jules Verne and Maurice Renard then found themselves sharing a same goal : to offer the reader the unknown, the elsewhere, be it purely ficticious (Renard) or perfectly possible but incredible (Verne), make them dream, be it by voyages circumventing the globe for one, or in the psyche, the soul and the marvellous for the other.

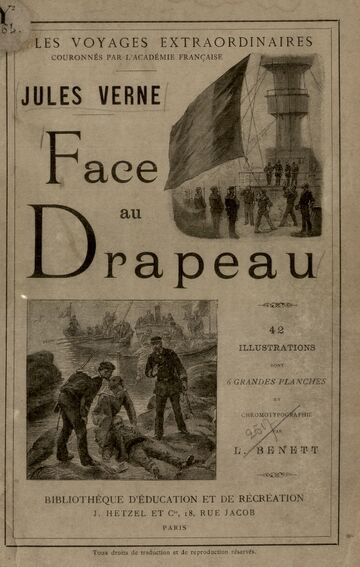

It would then perhaps be appropriate to ask ourselves if the divide between the concepts of literature of the two authors wasn’t a question of era: looking for the unknown and wonder was still possible in the real world (mostly in terra incognita, both geographically and physically) in Jules Verne’s time, whose avowed purpose was to enable the reader to travel (and learn), and this was no longer the case in the time of Maurice Renard, who then searched for another type of elsewhere and another type of dream. Moreover, in Jules Verne’s novels already, one could perceive a darkening and progressive mistrust of real science, which, as a brilliant instrument of progress and positivity in his early works, gave birth towards the end of the century to the character of the mad-scientist, and future key figure of the merveilleux-scientifique, incarnated in Face au Drapeau [Facing the Flag] (1896), with the possibility of total annihilation.

Front cover of Face au drapeau [Facing the flag], published by Hetzel (1896)

Further reading

- Consult Jules Verne’s works online or download them in EPUB format : Voyage au centre de la Terre[Journey to the centre of the Earth], Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours[around the world in 80 days], L'Île mystérieuse [the mysterious island], etc. You can also browse through the author’s manuscript of Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers[Twenty thousand leagues under the sea].

- Selections of « Les figures de la littérature pour la jeunesse [Literary figures in Children’s literature » regroup documents about Jules Verne : works, publisher’s hardback bindings, archives, manuscripts, etc.

- Read also : Fleur Hopkins, « Le merveilleux-scientifique : une Atlantide littéraire » and other posts in the Merveilleux-scientifique cycle.

- Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française was a free exhibition at the BnF (François-Mittérand site] from the 23rd April to the 25th August 2019.

Ajouter un commentaire