Emilie et Georges Romieu, La vie de George Eliot, Paris : Gallimard, 1930

In the second half of the 19th century, many critics became more seriously interested in the literary productions of women writers such as George Eliot, nee Mary Ann Evans, or Charlotte Brontë, hidden behind the pen name of Currer Bell. It must be said that the situation of women writers was far from simple, in an publishing context of anonymity and where women were relegated to typically feminine tasks, and excluded from the outside world:

Th. Karcher, Revue germanique, Paris : Librairie A. Frank, 1862.

Born in 1819, George Eliot was fascinated by the world of publishing very early on. Working for the London-based publisher John Chapman in 1851, she revolutionised an environment which was still essentially masculine. She was also a literary critic, translator and editor. She met the critic and philosopher George Henry Lewes, a married man with whom she maintained an affair for many years in spite of the moral constraints of the Victorian era. He encouraged her to write fiction, and it was while she was writing reviews for the literary magazine Review that she chose to adopt the pen name George Eliot.

Emilie et Georges Romieu, La Vie de George Eliot, Paris : Gallimard, 1930

Her first literary essay Scenes of clerical life. Janet’s repentance was published in Blackwood’s Magazine and was received favourably by the critics in 1857. Two year later, her first novel Adam Bede was published and prompted many questions: who was George Eliot really? Was the author a man or a woman? Debates as to the identity of the author were still raging in 1859, as can be seen in the following articles published in France:

O. S., Revue européenne : lettres, sciences, arts, voyages, politique, Paris, 1859, p. 4

One year later, in 1860, Eliot described the daily life of a brother and sister in The Mill on the Floss. There again, the rural setting, far from being a simple background, enabled the author to develop a critical view of the society, which was going through critical industrial mutations, at the expense of nature. The French critics were severe, and judged Adam Bede to be superior to The Mill on the Floss, which may also have reflected their disappointment following revelations about the identity of the author:

Gustave Masson, La Correspondance littéraire : critique, beaux-arts, érudition, Paris : L. Hachette et cie, libraires, 1859-11-10, p. 301-302

Of George Eliot, the public retained not only her particular interest in the daily life of rural England, but also her reflections on the harm of industrial innovations and on the evolution of society. Despite her fear that her novels would only be perceived as simple love stories, she surprised the readership by the power of her realism and the psychological depth of the characters she created. In her novel Silas Marner, the weaver of Raveloe, published in 1861, the writer this time portrayed the story of a weaver who lived in a rural community, and she developed the theme of individuals coping in the face of industrialisation. Like her fellow writers Charlotte Brontë and Elisabeth Gaskell, George Eliot didn’t hesitate to use her pen to defend her convictions and assert the rights of the citizens left behind by society’s progress:

Emile Chasle, Le Constitutionnel : journal du commerce, politique et littéraire, Paris, 1876-09-26, p. 3

This attachment to rural England with carefully painted portraits was very attractive to both the critics and the wider public alike, in France as on the other side of the Channel, testifying to the appeal of nature, as yet untouched by industrial mutations:

North Peat, Revue contemporaine, Paris, 1859, p. 542

Finally, in Middlemarch : a Study of Provincial Life (1871-1872), the reader discovered this time a gallery of characters who evolved in the fictional town of Middlemarch between 1829 and 1832. Here, realism was at the heart of the life of a community in the Midlands, and it enabled behavioural studies as well as it questioned the situation of women. A rich sociological network appeared in this microcosm of multiple intrigues, which made the novel a true laboratory where the author could reconcile sentiment and analysis. George Eliot bent the traditional rules of novel writing and opened up the Romanesque form by multiplying the points of view, thus offering a new definition of literary realism. The success of Middlemarch was huge. In fact, her critics often compared George Eliot to her French fellow writer George Sand because they both used the rural novel as a pretext to reflect upon wider social engagement and upon the future of society. Moreover, their respective lives scandalised the sense of morality of their contemporaries:

L. Qesnel, « Le roman contemporain en Angleterre », La Revue politique et littéraire : revue des cours littéraires, Paris, 1873, p. 16

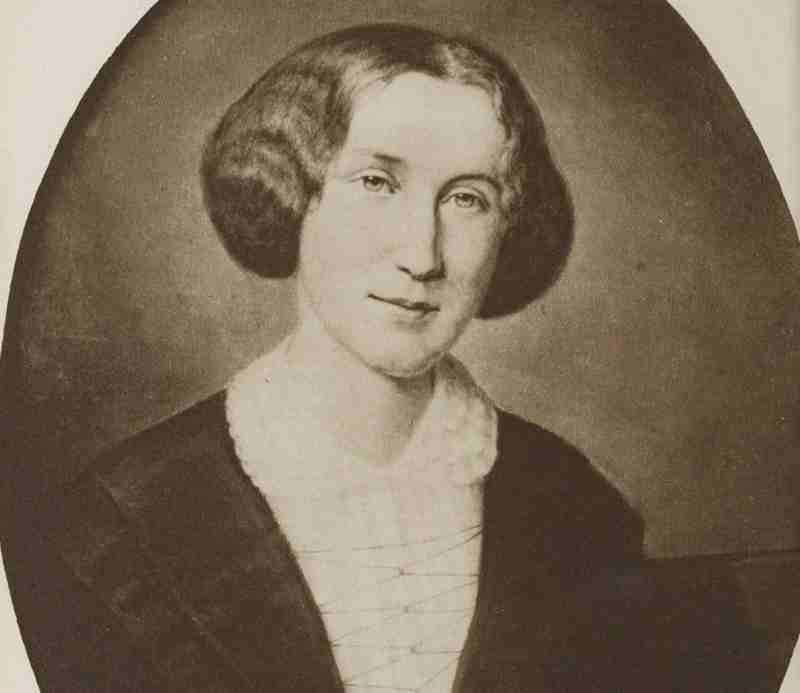

Just like George Eliot, George Sand used a pen name to disguise her identity. Nee Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin, Baroness of Dudevant, this French novelist was also a literary critic and a journalist. She advocated the defence of women and the struggle against the prejudices of a conservative society. Just like her British peer, she chose the countryside of the Berry as a setting for her novels which idealised peasant life (La Mare au diable, 1846 ; François le Champi, 1848 ; La Petite Fadette, 1849) in order to imagine an ideal society, free from conflict and class struggles.

Portrait of Georges Sand by Atelier Nadar, 1900

To Elme-Marie Caro, George Sand and George Eliot shared the same idealised view of the novel – nevertheless, the touch of humour present in the British novelist’s work offered an undeniably specific charm.

Elme-Marie Caro, George Sand : Paris, Hachette et Cie, 1887, p. 152

E. D. Forgues, La Revue britannique, septembre 1881, p. 148

At the end of the 19th century, English literature held an important place in France thanks to the publishing market which was invaded by successive waves of English novels from 1850 onwards, via Hachette’s « Bibliothèque des meilleurs romans étrangers » collection. Associated with Charles Dickens or Thomas Hardy, George Eliot became a reference who was mentioned more and more often. Her texts were analysed in literary journals on a regular basis, and she was a reference to many authors including Marcel Proust, who admired her novel The Mill on the Floss; he was very sensitive to the psychological finesse of the characters she depicted. But the resolutely modern nature of this British woman writer was truly recognised in Henry James’ tribute to George Eliot in the preface he wrote to The portrait of a Lady: “when one reads George Eliot’s novels, says James, the emotions, the tormented intelligence, the moral conscience of her heroes and heroines become one’s own adventure”. According to him, the Victorian novel is no longer the « shapeless monster » it was at its beginnings. Unlike the accounts of the Brontë sisters, the protagonists’ thwarted aspirations lay the path for a finer intellectual analysis, distancing themselves from emotions and revealing the anatomy of human psychology. It is with this particular reading of the works of George Eliot in mind that Henry James opens the way to a wider reception of the author by the public, which conferred an intellectual aura on the British writer.

Closer to home, critics participated in a re-evaluation of the work of George Eliot in the light of sociological and feminist approaches. Professor of English literature at Harvard University who specialises in British novels, Professor Leah Price writes about the difficulty women writers have to go beyond social relationships based on gender which are inherent to the organisation of literary genres.

As a fine observer of the transformation of rural populations into urban populations, George Eliot belonged to the great British authors whose life, like their work, contributed to challenge British society at a time of industrial and social development.

Further reading

Leaf through the manuscript of Middlemarch

Immerse yourself in the world of George Eliot

And read the previous blog posts in the series « English Women Writers »

Isabelle Le Pape

(translated from French by Claire Carolan)

Ajouter un commentaire