Merveilleux-scientifique: a literary Atlantis

From 23rd April to 25th August 2019, the French national library (BnF) showcased a little-known school of literature called “merveilleux-scientifique”, in an exhibition that covers the period from the genesis of the genre to its height, between 1900 and 1930. Rediscovering these texts, book covers, illustrations, and pictorial stories, revealed that they contained the seeds of some of the key themes of science-fiction such as we know SF today: extra-terrestrial alien invasions, augmented humans, cataclysms, mad scientists, xenotransplantation and artificial beings.

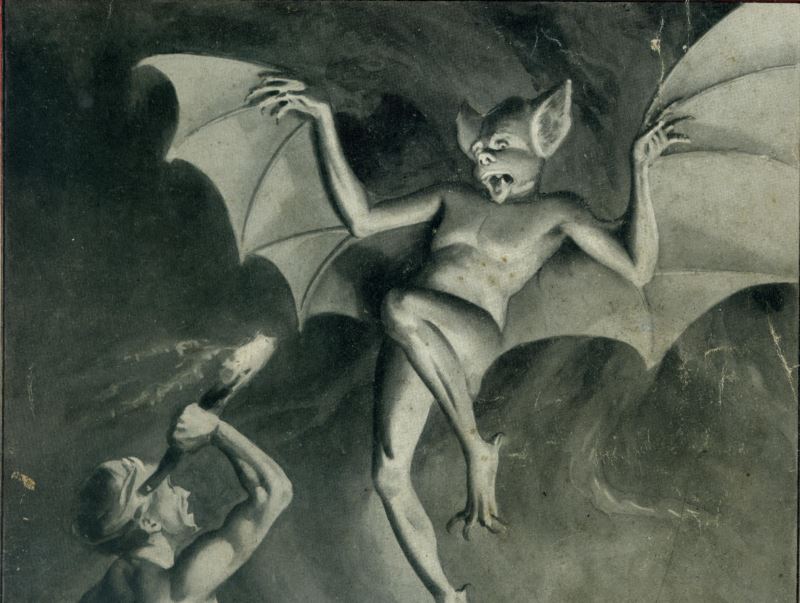

Le Prisonnier de la planète Mars [The prisoner of planet Mars] by Gustave Le Rouge, 1909

In 1909, the writer and master of thought Maurice Renard published a manifesto in the French journal Le Spectateur « Du roman merveilleux-scientifique et de son action sur l'intelligence du progrès » (Of the scientific-marvelous novel and its action upon the understanding of progress), whereby he sought to bring together a new school of literature. Author of Docteur Lerne, sous-dieu (Doctor Lern, Undergod), which involved brain swapping, and of Péril bleu (Blue peril), a tale of extra-terrestrial abduction, Maurice Renard made a distinction between “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction and the Vernean adventure novel, which he regarded as educational and scientifically unimaginative. He preferred to see Edgar Allan Poe, Auguste de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, J.-H. Rosny aîné or H. G. Wells as his peers. According to Renard, Verne’s “tale with a scholarly structure” didn’t aim to imagine the future, as suggested by Albert Robida, or to teach fundamentals of science against the backdrop of an adventure, as André Laurie or Paul d'Ivoi did around the same time, but rather painted the present in an offset manner that gave the reader food for thought.

“Merveilleux-scientifique” fiction also shared this ambiguous terminology with other literary models. Victor Segalen qualified Emile Zola’s experimental novel in that way derogatorily, as not scientific enough in his view. Maurice Renard and his peers took inspiration from it at two levels: they used their novels as an experimental laboratory, where they could study the effects of an environment on their heroes; and they also intended to bring into light the secret workings of man, in a literal way, in the form of reading another’s mind, or an internal journey.

[Excursions of Tom Thumb inside the human body and inside animals], 1886

The term « merveilleux-scientifique » was borrowed from Marcel Réja by Renard, who added a hyphen for style. It was also used at the same period by the physiologist Joseph-Pierre Durand de Gros to designate the scientific conversion of persuits that used to be marvellous or supernatural, and their study by respected scholars (Charles Richet, Marie and Pierre Curie, Camille Flammarion, Jean-Martin Charcot). The mysteries of the prolonged slumber of the fakirs, or “anabiosis”, unchain passions and the romantic imagination, while others take interest in the sixth sense rendered possible by « paroptic vision ». What if, behind the supernatural , only hid a form of science that we do not understand yet? Influenced by sciences and pseudo-sciences, fascinated by the discovery of X-rays by Röntgen, “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction presents itself also, as per Maurice Renard’s own terminology, as “parascientific” fiction.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, with the work of Pierre Versins and the publication of the journal Fiction that the field of “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction was rediscovered by specialists of speculative fiction. This omission by the critics can be explained by several factors, as much to do with Maurice Renard’s difficulty to get his literary model recognised – as he kept changing its name between 1909 and 1931, to appeal to a greater readership - as to do with the arrival in France of American science-fiction in the 1950s. Thus, the “merveilleux-scientifique” genre – as well as witnessing the existence of novelistic patterns before their development in later American science-fiction – is interesting to rediscover because it is a witness to the mutation in the scientific novel, favoured by an era that was fascinated by the mysteries of para-sciences. Re-reading “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction today is also about understanding how the turn of the century, rich in the popularization of science, saw the birth of many imaginary writings, even inventing new sciences.

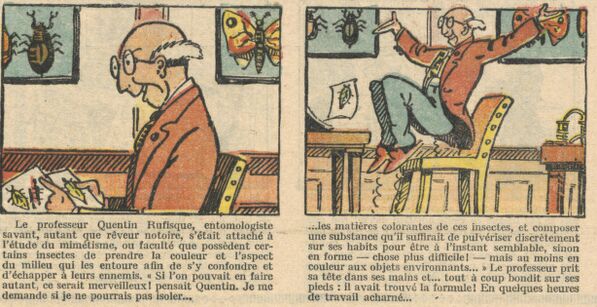

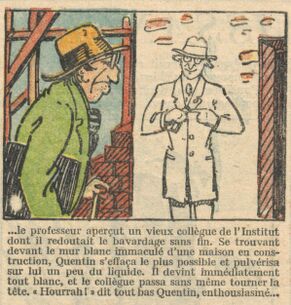

The exhibition Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française (« merveilleux-scientifique » fiction. A French style of science-fiction) offers both the rediscovery of this little-known genre, recently republished by the BnF’s collection « Les Orpailleurs », with titles such as Le maître de la lumière (The Master of Light) by Maurice Renard or Trois ombres sur Paris by H.-J. Magog, and the identification of some of the major authors of the genre such as Maurice Leblanc, Guy de Téramond, J.-H. Rosny aîné, Maurice Renard, Jean de La Hire, Octave Béliard, Léon Groc, Gustave le Rouge, Jacques Spitz. Their stories, full of inventions, fascinating images and in tune with the most recent scientific discoveries and their applications, show us how fertile the imagination of French authors was at the time.

Further reading

Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française is a former exhibition at the François-Mitterrand site of the national library, from 23rd April to 25th August 2019.

To read “merveilleux-scientifique” stories on Gallica, here is a treasure map in the form of an online bibliography.

To enjoy the visual and iconographic wealth of the movement, check out this account on Instagram

Ajouter un commentaire