A life of writing and adventures

According to the scant records available, Aphra Behn, nee Johnston, was born in Canterbury and baptised on December 14, 1640. Very few verifiable sources recount her youth. One version tells of a barber’s daughter. In the 1660s she allegedly travelled to Surinam, which was then a Dutch colony of South America occupied by the English. However, we are not certain as to whether this trip actually took place in real life, despite it inspiring her most well-known novel Oroonoko (1688). Upon her return, she married a merchant whom we assume to have been Dutch and took the name “Mrs Behn”. However, she is widowed in 1666 at the age of 26. She is introduced to the court of Charles II, where the details of her stay in Surinam appealled to the aristocracy. Then she was sent to Antwerp, under the pseudonym of “Astrea”, where she collected information that she encrypted before it sending to London. She made use of her charm and wits:

Raoul Deberdt, « Les femmes journalistes »,

However, this was not a very lucrative activity. The young woman returned to England a pauper, and had to spend time in a debtors’ prison. Upon her release, she published her first play to support herself:

Le Mariage forcé (

The Forced Marriage, 1670) was a great success. She invented a pantomime by making the actors wear masks in

L’Empereur de la lune (

The Emperor of the Moon, 1687), and she became friends with the actress Nell Gwynn, mistress of the king, thus gaining in popularity, and publishing numerous plays such as

The Plays, histories and novels of... Mrs. Aphra Behn, with life and memoirs.

Along with

Susannah Centlivre (1669-1723) and

Mary de la Riviere Manley (1663-1724), Aphra Behn is then one of the most renowned women writers of the Restoration period in England. Her enigmatic personality and being accused of being a spy attracted heavy criticism from her contemporaries, all whilst being protected by Charles II:

Aphra Behn’s contribution to the anglophone novel

In the 18 plays she published, such as

The Rover (1677 and 1681), Aphra Behn wrote about arranged marriages, the consequences of which were often devastating for the lives of the young women. In writing 13 novels, including the epistolary novel

Love-Letters between a nobleman and his sister (1683), she contributed to the birth of the English novel, which at this stage, is still a nascent genre made from diverse forms of writing that used undefined narrative logic and plot outlines. During this period of the English Restoration, written works were either very austere, such as

Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) by

John Bunyan, inspired by travel accounts such as

Daniel Defoe’s

Robinson Crusoë , dense and rich in biblical references such as in

Paradise Lost (1677) by

John Milton or, quite the opposite (

Sodome by Count

John Wilmot Rochester).Very popular both in its form and content, Aphra Behn’s epistolary novel made its mark as a model of the genre and foreshadowed the enthusiasm of the readers for this literary tradition.

Being perfectly fluent in French, Aphra Behn was also a translator, namely of the

Maximes by

La Rochefoucauld (

Epictetus Junior or MAXIMES of Modern Morality in Two Centuries, 1670 and

Miscellany, Being a Collection of Poems by several Hands. Together with Reflections on Morality or Seneca Unmasqued, 1685). She also translated the

Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes by

Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle. However, the translations produced were more like literary rewritings in the sense that she freely set La Rochefoucauld’s statements in a fictional context of a love story between two characters: Aminta and Lysander. Published in 1694, an anonymous translation of the French edition was also attributed to Aphra Behn (

Moral Maxims and Reflections in four parts).

Slavery and colonialism : the success of Oroonoko

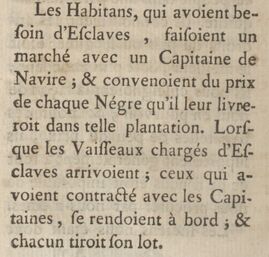

Aphra Behn’s greatest literary success is the novel Oroonoko or the royal slave (1688), in which she exposed western hypocrisy and the slave trade, leading to the first philosophical novels. Based on her stay in South America, the plot is staged far from the London central government, in Surinam, which was then a British colony before the Dutch took it over.

In the 17th century, England, like other European countries, actively took part in the slave trade, namely in Barbados. The

Company of Royal Adventurers of England Relating to Trade in Africa Charter (1663) officially recognised slave trade in the British Empire under Charles II. In most European countries who had colonies, tribes of first settlers and slaves were seen as primitive people which had to be educated or savages to be exterminated.

Aphra Behn, Oronoko, Versailles : S. Dasier, 1779, p. 12

Behn’s novel foresaw the way we look at the triangular trade today. In her account, real historical figures appeared alongside the description of the captivity of the fictional African Prince Oroonoko who was sold as a slave to the English colonies. Many details aimed to furnish a background of truth to the story, underlining the authentic quality of the narrative. Aphra Behn depicted not only an African man in an exotic setting, but she also gave him the noblest of virtues, in contrast to the corruption of the Europeans who deceived him and reduced him to slavery. Unlike the written accounts of her contemporary explorers, the portrait of Oroonoko is not based on a historical figure who actually existed, but testified to an imaginary construct of an African, of whom descriptions were rare in publications at the time. Here, he was idealised and became the symbol of the denunciation and criticism of slavery. Thus he prepared the ground for the concept of “noble savage”. Despite being admired by readers of the 18

th century, Oroonoko’s grotesque violence was strongly criticised by judges of good taste and morality. An interesting blend of travel writing, sentimental outpouring and anti-slavery tale, its modernity isn’t revealed until the 20

th century. Her novel was used as a model for abolitionists and inspired

Voltaire’s

Candide, thus playing an important part in struggles against slavery at a time when this trade was prospering.

A few decades earlier, in France,

L'Histoire de Louis Anniaba (1740) was the first French novel to feature a sub-Saharan African as the hero, Louis Annabia, not long before the first translations of

Oronooko were published. It must be said that the erstwhile thirst for travel writing was favourable to the introduction of new exotic characters, which seduced the readership. For a long time, the origin of “the myth of the good savage” was attributed to

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, when in fact he was just

relaying a figure that appeared in Oroonoko.

The fortunes of Aphra Behn in literary history

Often relegated to the back bench in history of literature textbooks, Aphra Behn nevertheless piqued the curiosity of her contemporaries and of those who studied the genesis of the novel in England. The novel as a genre expanded as the book market grew. It is therefore surprising that textbooks forget to mention the written work of this free woman, great traveller and adventurer, who was one of the very first female authors to be able to live off her own writing. It has to be said that Aphra Behn didn’t leave anyone indifferent, skipping easily between genres, publishing tragi-comedies (

The Amorous prince, or the Curious husband, 1671), plays written in the style of Molière (

The Rover,

Sir Patient Fancy) or even plays that reflected the triumph of Charles II ((

The City-heiress, or Sir Timothy Treat-all, 1682). For those who study her novel

Oroonoko, it is noticeable how English literature opened up to a new interpretation of ethnic stereotypes. In a French translation by

Pierre-Antoine de La Place, the spelling of the name of the hero is simplified to “Oronoko”, intently less exotic than the original to make the text more palatable to French taste. This translation played a big part in making Europeans, and especially European writers, aware of the fate of Black People and slavery. Readers would shudder for the heroine Imoinda, condemned to slavery for wanting to escape the abuses of the patriarchy. However, La Place took the liberty of replacing the final ordeal, loaded with gothic horror, by a less terrifying and more idealised ending.

Raoul Deberdt, « Les femmes journalistes »,

Forgotten by the historians of literature, criticised for her liberty of tone and the indecency of her plays, denigrated in favour of more visible male authors, Aphra Behn is undoubtedly to be rediscovered. The work of critics and researchers have given her a new form of celebrity, particularly in the eyes of Virginia Woolf, who made her out to be one of the first self-sufficient female writers, by stating in A Room of one’s own (1929) :

“All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds”.

Further Reading

And read the previous blog posts in the series « English Women Writers »

Isabelle Le Pape

(translated from French by Claire Carolan)

Ajouter un commentaire