Wireless telegraphy

Man has always sought to communicate from a distance – be it by visual means, (smoke signals, torches, kites, flags…), sound (shouts, drums, tam-tams, trumpets, bells….) or by the means of carrier pigeons. Wireless telegraphy appeared towards the end of the 19th century. It was the fruit of several European and American inventions. It fed the imaginations of writers of the merveilleux-scientifique literary movement, initiated by Maurice Renard, who gave birth to strange machines and uncanny phenomena.

In 1794, Claude Chappe (1763-1805) developed the optical telegraph , made up of 92 match signals, encoded thanks to pivoted indicator arms. The machine was fixed on towers or heights. Close to the coastline, it took the name of semaphore.

In 1888, the German Heinrich Hertz (1857 – 1894) highlighted the electromagnetic waves discovered by the Scotsman James Clerk Maxwell (1831 – 1879). These radio waves were known in French as “ondes hertziennes”. Two years later, the French physicist Édouard Branly (1844 – 1940) observed the conductive properties of iron filings (powder). He devised a machine capable of detecting them, coined a “coherer” by the Englishman Oliver Lodge (1841- 1950), who explained the phenomenon of radio conduction. On the 7th May 1895, the Russian Alexandre Popov (1895-1906) developed the transmitter and antenna that were the basic elements of wireless telegraphy. Other scientists, engineers and brilliant tinkerers argued over inventions and patents.

The Italian Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) managed to synthesize previous works. He tested the first wireless transmission or “wireless telegraph” as he called it, and succeeded in emitting the first signals in 1895. He created his own company in England in 1897, the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company. After many improvements, he managed to send a first radio telegram via the Pas-de-Calais, in 1899. The wireless was born, and found its first application in communications between ships at sea. That same year, the first cross-channel link between Folkestone and Boulogne was made. It was at that time that the SOS (Save Our Souls or Save Our Ships), to send an alert in case of peril was established. In 1902, 70 ships were equipped with wireless and they could communicate with 25 coastal stations. In 1907, the first transatlantic liner was equipped with it, and soon all the other lines were too. The first rescue mission that was enabled by the wireless took place in 1909, following the collision of two ships: the Republic and the Florida.

The Titanic

Like all other transatlantic ships, the Titanic was equipped with wireless. It was Marconi’s company that was in charge of the telegraphic installations aboard the ship. After reparations following a breakdown of the device, both telegraph operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were busy sending personal messages or business messages on behalf of the richest passengers from the beginning of the crossing on April 10th, 1912. Urgent messages coming from other ships nearby signalling drifting ice and icebergs were received but not transmitted to the commander Edward Smith. Just before the collision, the Californian, sent a last message at 11.00pm. The telegraph operator cut them short, as he was liaising with Newfoundland and too busy sending passenger messages. On April 14th at 11.40 pm, the Titanic collided with an iceberg and sank about 2 hours later. Nevertheless, the wireless did allow to send for help, and thus saved human lives.The Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower, which was built for the universal exhibition of 1889 didn’t get good press and was threatened with destruction. In 1903, Gustave Eiffel made it available to military engineers, and financed the military wireless tests lead by polytechnician Captain Ferrié himself. At the time, the army gave preference to Chappe’s optical signals or carrier pigeons. The tower had the highest antenna in the world. The transmission distance could reach 400 km. On January 21st 1904, the Eiffel tower became a wireless station for military radiotelegraphy.

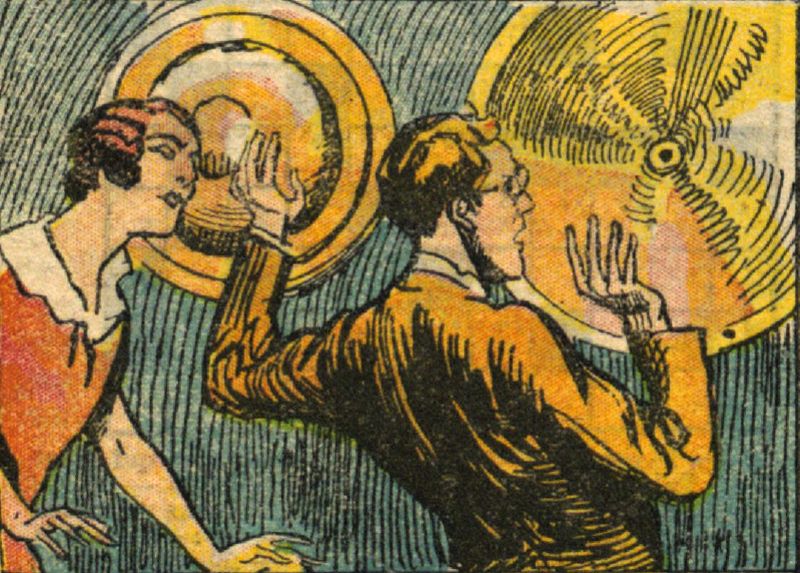

The wireless and the First World War

Right from the start of the First World War, the wireless telegraph transmitters were controlled by the army. Located at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, the centre for radiotelegraphy of Paris was tasked by Gustave Ferrié to listen in on enemy waves. A key man of the military radio, he was the author of La télégraphie sans fil et les ondes électriques [Wireless telegraphy and electric waves]. The conflict contributed to advances in wireless technology and the protection of information thanks to cryptology.In the aftermath of the First World War, posts equipped with crystal radio detectors enabled the capture of waves emitted from the Eiffel Tower and listening to meteorological bulletins and news bulletins. At first, the messages were coded in Morse : tap…tap…tap… Towards 1921-1922, it became possible to hear voices or listen to music programs. The wireless then became the radio.

The public gradually adopted the wireless, and it became an everyday object. The object fascinated people, and it had a place of choice in their living rooms. Advertisers took hold of it. Even writers become interested in the wireless, and so, it entered the realm of literature.

Wireless radio in the imagination

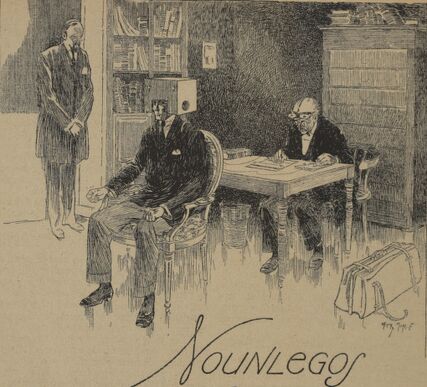

This technical invention nourished the imagination of writers of the twentieth century. Their mad scientists came up with more or less eccentric uses for it. The invention of the wireless radio was diverted to many other functions: mind reading or telepathic communication, and even to contacting aliens.Raoul Bigot (1874 – 1928) published Nounlegos in January and February 1919 in the journal Lecture pour tous [Reading for all]. It was republished in 1921 by the Pierre Laffitte publishing house under the title “Nounlegos, the man who could read inside brains”. Nounlegos was a scientist that invented a “special electric machine” to examine brains and read minds. He went to a judge to offer his invention which, according to him, would help justice to solve criminal cases. They were inspired by wireless radio, with a transmitter and a receiver. The suspect would put on a box-shaped helmet. The inventor, wearing a shield on his forehead, manipulated the other machine and scribbled signs in the shape of a secret language on a blank sheet of paper, with a stylus. After studying medicine, the scientist dedicated his time to inventing this machine, capable of reading minds in the service of justice.

The novel Satanas by Gabriel Bernard was published in installments in the Petit journal between April 29th and August 11th1922. The author presented the members of a brotherhood, “the Knights of the Star” whose distinctive feature was a pink star-shaped organ that enabled them to communicate by telepathy and read minds, just like a wireless radio. It is the Human wireless radio that enabled human brains to engage in distance communication with radio waves. Telepathic energy spread like these waves.

The comic « La T.S.F. interstellaire [The interstellar wireless] », by Val, staged Professor Bornilas who dedicated all his fortune to the invention of a machine that emitted waves as far away as 70 000 000 leagues to reach Mars, and a matching receptor. But the old professor did not despair of getting a reply. His daughter and his student then devised a plan by playing the role of Martians and communicating with the professor, until the day Martians actually did communicate with them. The scientist had no idea of the trick that was played on him, and the news of his discovery travelled the world.

The wireless telegraph reduced the distance between men by enabling them to communicate amongst themselves. Writers seized it to create wonderful stories, opening up technology to the imaginary world.

Pour aller plus loin

Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française was a free exhibition that could be visited on the François-Mitterrand site of the national library from the 23rd of April to the 25th August 2019 during the opening hours of the library.Read articles dedicated to the "Merveilleux-scientifique Cycle" in the Gallica Blog.

To read merveilleux-scientifique stories in the digitized collections of Gallica, here is a treasure map, in the form of an online bibliography .

To enjoy the visual and iconographic wealth of the movement, check out this Instagram account.