In reality, it wasn’t until the 1950s that long-lasting whole organ transplantation was mastered in humans. Some operations such as head or brain transplants remain pure fantasy. But what was the state of knowledge on transplants in the first decades of the 20th Century, at the time when merveilleux-scientifique literature thrived?

First let us recall that, in medicine, transplantation consists of the removal and implantation of a whole organ (heart, lung, kidney…). A graft, on the other hand, involves partial implantation (skin, cornea). The term allograft is used for organ transplantation between two individuals of a same species, and the term xenograft for that between individuals of two different species.

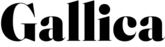

Prior to the 20th Century, graft attempts were made, but they often failed. In the 16th Century, Gaspare Tagliacozzi was successful with autografts (grafts where the donor and recipient are the same person) of the nose, but failed with allografts. In 1869, Jacques-Louis Reverdin succeeded in performing the first skin graft. The nineteenth century saw the development of graft experiments on animals which lead to the first successful autograft of the kidney of a dog to its own neck in 1902. The kidney graft is very popular: its removal is easy (the remaining kidney being enough to ensure survival), and its excretory function enables the appreciation of the proper functioning of the graft. We will see that the first attempts of transplantation in man also involved kidneys, implanted on the elbow or on a thigh.

The beginning of the 20th Century was an intense period of experimentation, applying ethics that appear rather questionable nowadays. The research benefitted from the progress of past centuries in the areas of anesthesia, antisepsis and asepsis. But the implantation of an organ also requires the mastery of vascular suturing to stitch the vessels and ensure the blood flow to the graft, which no surgeon knew how to do at the end of the 19th Century.

In this area of research, the publications of the Lyonese School, led by Mathieu Jaboulay and Alexis Carrel, were decisive. From 1896 to 1898, Mathieu Jaboulay researched sutures and arterial grafts. Alexis Carrel developed a more efficient technique to suture end to end with support threads by triangulation. He detailed his method in an article published in 1902. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1912 for his work on vessel suture and organ transplantation. Although nowadays Carrel is sadly more associated with his theories on humankind, his research at the beginning of the 20th century did contribute to the development of vascular surgery and the technique of triangulation as we know it today.

We only know that the method that I have just described allows in a rather simple fashion to perform the difficult anastomosis that is required by organ transplantation.

In 1906, Mathieu Jaboulay performed the first xenografts of pig or goat kidneys on the elbows of two women who suffered from kidney failure, in order to “establish a functional supplement for urinary secretion, by installing a foreign but healthy kidney.” These attempts failed. Still in the first years for the twentieth century, Alexis Carrel transplanted various organs on dogs, but all the test subjects died after having rejected the grafts.

Indeed, mastering the vascularization of the graft did not suffice. Experiments showed that excluding autografts, biological incompatibility does not enable survival of grafts. The body defends itself against foreign bodies. In 1933, after a long phase of animal testing, the soviet surgeon Yuri Voronoy defined rejection as an immunological event. He was the first to perform a human kidney graft from a deceased donor. The kidney was grafted on the thigh of the recipient and not in the abdominal cavity. Voronoy performed six allografts in total between 1933 and 1949; all ended in failure.

It was only with the works of Jean Dausset in 1952, and the discovery of the HLA system (human leucocyte antigens) that the mechanism of graft rejection was really explained. The development of immunosuppressive therapies enabled the durable acceptance of the graft. But the research performed in the area of immunology during the first decades of the 20

th century paved the way. The period before the first world war was particularly rich in discoveries, crowned by several Nobel prizes in medicine: the discovery of

blood groups in 1901 by

Karl Landsteiner (Nobel prize 1930) ; the discovery of

anaphylaxis in 1902 by

Charles Richet (Nobel prize 1913) ; the discovery of the antigen-antibody complex by the German

Paul Ehrlich; and the discovery of

phagocytosis as a means of controlling bacteria by

Élie Metchnikoff (co-laureates of the Nobel prize in 1908) .

This research, which was sometimes austere, didn’t meet a very large audience at the time of its publication. In Paris in the 1920s, the public was more interested in the graft of monkey testicles on humans, suggested by

Serge Voronoff. After having experimented with grafts on animals, he started working on xenografts on humans in 1920. According to him, introducing very thin

slices of monkey testicles in a man’s scrotum would be enough to return physical and intellectual vigor, rejuvenate and grant longer life to a man. As a skilled popularizer of science, he increased the number of his lectures and used new course materials such as

photography and films. Numerous articles were published in popular newspapers and the more specialized journals:

Le Figaro, L'Humanité, Paris-Soir, Le Matin, Le Concours médical or la

Revue neurologique…The press started using the term “

to voronoff” as a verb or in other forms, in a tone of irony. The works of Voronoff inspired

works of fiction and

satirical drawings, as well as plays and

songs.

The reactions of the medical community were mixed: some colleagues used his methods, but others began to strongly criticize his lack of ethics and the questionable results he obtained. Nowadays the success of such grafts sounds biologically unbelievable, but the practice was of its time. The role of hormones was discovered, as well as the use of organ extracts (called

opotherapy] was common. In different editions of the

Vidal Dictionary at the time, a dictionary which references marketed medicines in France, a number of opotherapeutic preparations which contained extracts of the

thyroid gland,

cerebral substance or a

young cow’s ovaries were listed.

It is not surprising that the subject of grafts, which carries interrogations on the future of human beings, transformed by the addition of foreign bodies, inspired authors of the merveilleux-scientifique genre, chiefly Maurice Renard, relentless promoter of this literary movement. In 1908, in

Le Docteur Lerne, sous-dieu [

Doctor Lerne, sub-god], he imagined a brain swap between two individuals, which resulted in an exchange of personalities. In this story, Otto Klotz, who is doctor Lerne’s assistant, steels his body by exchanging their brains. The issue of xenography, which is likely to endow the receiver with the physical abilities of another species, is addressed by another merveilleux-scientifique author: Jean de la Hire. In a story entitled

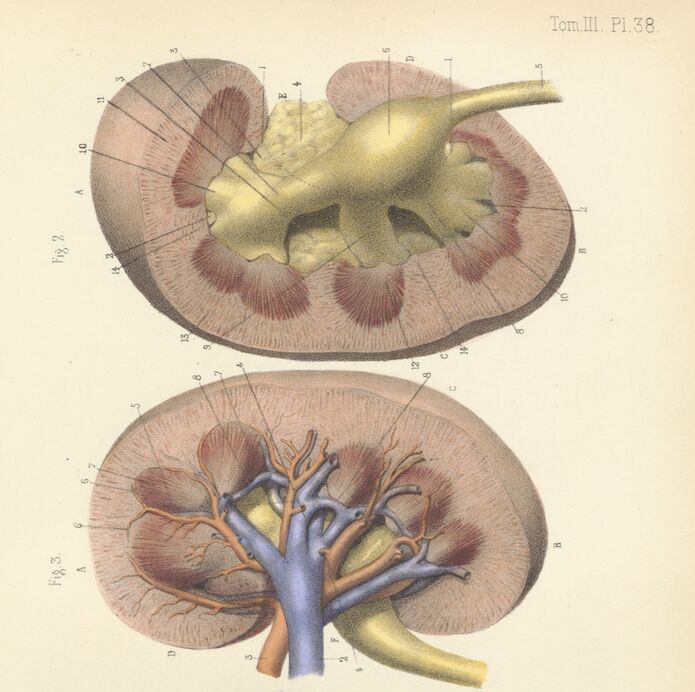

L'homme qui peut vivre dans l'eau, that was published in installments in the newspaper

Le Matin between the 26

th July and 28

th September 1909, a mad scientist grafted a shark’s gills to a baby, to make it into a man-shark.

It is once more question of the violation of personality in Maurice Renard’s Les mains d'Orlac [The hands of Orlac] which appeared in installments in L'Intransigeant between May 15th and July 12th 1920. In this story, a pianist who was victim of a train accident, Stephen Orlac, was the recipient of the transplant of the hands of a criminal, and he believed he was inhabited by the spirit of the assassin. Maurice Renard also wrote about the theme of artificial organ transplants in L'homme truqué [The modified man], published in 1921 in the magazine Je sais tout. Here, the protagonist Jean Lebris, who lost his eyesight during the Great War, is implanted with electroscopes in place of his eyes, which enabled him to see electricity. A repaired, transformed, altered, augmented man...One century later, these themes broached in the merveilleux-scientifique stories are still current in literature.

Pour aller plus loin

Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française was a free exhibition that could be visited on the François-Mitterrand site of the national library from the 23rd of April to the 25th August 2019 during the opening hours of the library.

Read the series of blog posts dedicated to the " Merveilleux scientifique Cycle" in the Gallica Blog.

To read merveilleux-scientifique stories in the digitized collections of Gallica, here is a treasure map, in the form of an online bibliography .

To enjoy the visual and iconographic wealth of the movement, check out this Instagram account.

Translated from French by Claire Carolan