From physiognomony to phrenology

The Merveilleux-scientifique literary movement systematically took as a starting point a law of physics, chemistry or biology, and altered it.

We will see here how it was influenced by scientific or pseudo-scientific theories such as physiognomony and craniology or phrenology, whose common denominator was to claim a better knowledge of the human being thanks to its physical particularities.

Already back in Antiquity, it was considered that the character of a man could be perceived by the study of the traits of his face. It was Johann-Kaspar Lavater, a Swiss theologian (1741-1801), who theorized his method of morpho-psychology under the name physiognomony. His work was translated into French: Essai sur la physionomie ou l’art de connaître les hommes [Essay on physiognomony or the art of knowing men].This theory was very popular with 19th Century novelists such as Balzac, in the Comédie humaine.

A classification of men based on their physical traits was derived from physiognomony, and published by the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso in his work entitled :

L’homme criminel [The criminal man] / Cesare Lombroso, 1887

At a time where racial profiling was not punished, the lambrosian theory flourished. Still with the intention of classifying individuals who were apprehended by the police, Alphonse Bertillon, an employee of the photographic service of the police headquarters, imagined in 1883 proceeding with 9 bone measurements, including the length of the head from the cranium to the forehead, and the width of the head from the left temple to the right. “Bertillonnage” as it was called, enabled the anthropometric identification of the inmates. The Bertillon method was emulated – for example by Louis Marchesseau in 1911 with Le portrait parlé et les recherches judiciaires [The spoken portrait and judiciary searches]

Extract from : La Photographie judiciaire [Legal photography] by Alphonse Bertillon. 1890

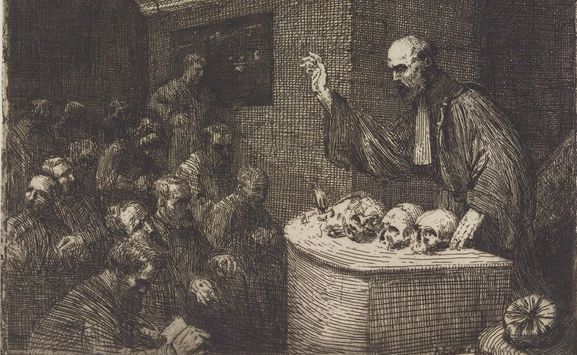

At the beginning of the 19th century, German doctors Franz-Joseph Gall (1758-1828) and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim (1776-1832) got the idea of determining the psychological profile of individuals no longer by the study of their physiognomy, but by the observation of the bumps on their heads, method that was coined ‘craniology’ in a first instance. From 1810 to 1819, they wrote a book in 4 volumes on the subject: Anatomie et physiologie du système nerveux en général et du cerveau en particulier, avec des observations sur la possibilité de reconnaître plusieurs dispositions intellectuelles et morales de l'homme et des animaux par la configuration de leurs têtes [Anatomy and physiology of the nervous system in general and of the brain in particular, with observations on the possibility of recognizing the intellectual and moral dispositions of man and animals by the configuration of their heads]. Subsequently, an English disciple of Gall, Thomas Forster (1789-1860) renamed this line of thought under the better known term of phrénologie. Gall based himself on four hypotheses: the shape of the skull reflects the shape of the brain; the mind can be split into 27 distinct faculties; these functions are themselves situated in specific areas of the brain; the characteristics of human behaviour can be predicted in relation to the development of protuberances on the head. In the 19th Century, the publication of treaties in phrenology increased. In 1837, Théodore Poupin claimed that he combined both methods in his treaty : Caractères phrénologiques et physiognomoniques des contemporains les plus célèbres, selon les systèmes de Gall, Spurzheim, Lavater, etc. [Phrenological and physiognomical characteristics of the most famous contemporaries, according to the systems of Gall, Spurzheim, Lavater, etc.]

Despite the peers of the German anatomist working hard to demonstrate the inexactitude and the pseudo-scientific nature of phrenology, this method was very popular in the second half of the 19th Century: it even went as far as evaluating the compatibility of future spouses depending on the configuration of their skulls. Raoul Bigot, a Merveilleux-scientifique writer, staged a story that was published in instalments in Lectures pour tous , where a fictitious character named Nounlegos was presented as a scientist in phrenology who had developed a headdress that was capable of reading the human brain.

Generally speaking, craniology or phrenology had a great influence on the writers of the Merveilleux-scientifique movement, triggering a true fascination for the brain and its contents, which they subjected to all sorts of strange experiments. In 1900, the serial writer Henry Desnar described in great detail the modelling of a skull by a certain Doctor Cornelius. In L’Homme qui peut tout [The Man who can do everything], Guy de Téramond imagined freeing the cerebral circumvolutions of a criminal to make him a superior being. In Trois ombres à Paris [Three shadows in Paris] by HJ Magog, again we found this mad desire to create super intelligent beings, in the form of scientist Fringue, supposed to have succeeded in isolating the fluid that produced thought. In On vole des enfants à Paris [Children are stolen in Paris] by Louis Forest, this time it was by implanting a grain of radium in the head of ordinary children that the author created super humans.

Thus, in the Merveilleux-scientifique imagination, the human body and particularly the brain, became malleable material in the hands of mad scientists: it became possible to map them, explore them in every detail, to knead the matter and mould it at will. But as Maurice Renard, the leading figure of this literary current summarized:

When Man alters Life, he creates monsters.

Further reading

- Le merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française was a free exhibition that could be visited on the François-Mittérand site of the national library from the 23rd of April to the 25th August 2019 during the opening hours of the library.

- Read articles dedicated to the "Merveilleux-scientifique Cycle" in the Gallica Blog.

- To read merveilleux-scientifique stories in the digitized collections of Gallica, here is a treasure map, in the form of an online bibliography .

- To enjoy the visual and iconographic wealth of the movement, check out this Instagram account.

Translated from French by Claire Carolan