« Merveilleux-scientifique » in the French literary landscape

Unlike American short stories, « merveilleux-scientifique » stories were not published in identifiable publications such as the pulp-magazines that were dedicated to American science fiction in the 1930s. Nevertheless, magazines and publishers played an important role in the dissemination of “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction

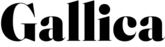

Jean de La Hire, La roue fulgurante[The fiery wheel] [1908], book cover illustrated by Paul Thiriat, in the collection « Le Livre de l'Aventure », Paris : J. Ferenczi et Fils, 1922

In the United States, magazines such as Amazing Stories, Astounding Stories or Wonder stories were particularly conducive to the growth of American science-fiction, by the existence of a fandom, an identifiable leader in the dialogue with the authors, assigned illustrators and a publication of reference. Nevertheless, in France, several periodicals, magazines or publishers, often of mass-circulation, published many “merveilleux-scientifique” stories, although none of them were labelled as such at the time in a section of the magazine or as part of a collection.

Amongst these periodicals, let us first mention L’Intransigeant, founded by Eugène Mayer. He printed several stories by Maurice Renard and Léon Grox, between 1919 and 1933, including some that are regarded as classics of the genre such as Le péril bleu (Blue peril) by Maurice Renard, which is the story of the abduction of Earthlings by invisible aliens, and On a volé la Tour Eiffel! (The Eiffel Tower has been stolen!) by Léon Groc, which is about a scientist who devised a way to transform iron into gold.

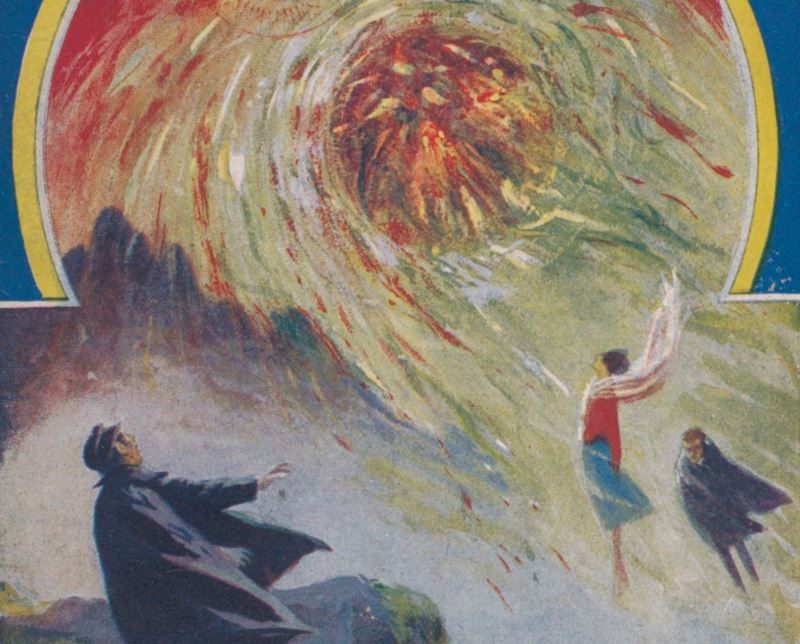

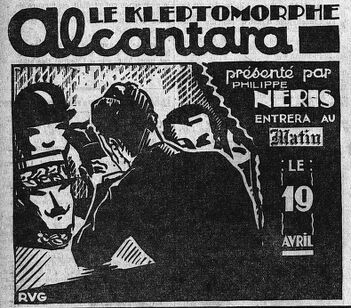

Between 1906 and 1943, Le Matin, a newspaper which was inaugurated by Chamberlain & Co, published tales and stories in several installments by Maurice Renard, by Jean de La Hire and by Gaston Leroux. In Les dompteurs de forces (The force tamers), Jean de La Hire staged an Aztec secret society that wanted to take control of the world, while Lucifer told of the actions of an enemy of the Nyctalope, Glô van Warteck, who devised a “teledynamo” which amplified his mental powers. The paper distinguished itself by its beautiful advertisements, illustrated by Gino Starace, that were intended to praise the publication of the next installment in its pages, such as La roue fulgurante (alien abductions), L’homme qui peut vivre dans l’eau (half man-half shark), or Alcantara (body snatcher) by Jean de La Hire.

Advertissments illustrated by Gino Starace for La roue fulgurante[The fiery wheel] by Jean de La Hire, in Le Matin, 10th April 1908

and for L'homme qui peut vivre dans l'eau [The man who could live underwater] by Jean de La Hire, in Le Matin, 18th July 1909

and for L'homme qui peut vivre dans l'eau [The man who could live underwater] by Jean de La Hire, in Le Matin, 18th July 1909

Advertissment illustrated by RVG for Alcantara by Philippe Néris (pseudonym of Jean de La Hire), in Le Matin, 1923

Between 1927 and 1939, Maurice Renard published in this same journal more than 600 tales, some whodunits, some love-stories, some supernatural stories, and some pseudo-“merveilleux-scientifique” stories, in which scientific discovery was nothing but a lure. Thus, Le spectre photographié isn’t about a ghost but an X-ray photograph, Le monstre du Loch Ness turns out to be the projected image of the lake creature; L’aventure scientifique d’Ambroise Peupiot does not take the protagonist to the fourth dimension but to a desert island to escape his wife; La nuit surnaturelle intimidates a child, who thinks they are experiencing something against nature, when in fact it is nothing more natural than a woman giving birth. Another paper is to be mentioned: Excelsior, founded by Pierre Laffitte, published many stories by Guy de Téramond (L'épinard conscient, La dernière invention du reporter), L'autobus évanoui by Léon Groc, as well as a text by André Couvreur and Michel Corday, about the adventures of a telepath (The Lynx).

Two main magazines competed for the publication of these short stories: Je sais tout, founded by Pierre Laffitte, and Lectures pour tous, founded by Victor Tissot. Other than the short stories, they both published speculative articles, guessing where science was heading (habitability of planets, communication with Mars, future innovations, etc.). Between 1907 and 1922, short stories by Maurice Renard, J.-H. Rosny aîné, Maurice Leblanc, Michel Corday, Paul Arosa and Jules Perrin were published in Je sais tout. Amongst all those stories emerged some that were representative of the “merveilleux-scientifique” vein. In Le mystérieux Dajan-Phinn by Michel Corday, a scientist had put together an artificial being, while the scientist in Paul Arosa’s Mystérieuses études du professeur Kruhl keeps a slaughtered head alive thanks to an electric machine and fresh pig’s blood. In La force mystérieuse by J.-H. Rosny aîné, or Les trois yeux by Maurice Leblanc, mysterious optic phenomena take place. In the former, a spectrum of light weakens under the influence of cosmic interference, and causes a spurt of madness and carnivorous behavior across the surface of the globe. In the latter, men from Venus send images of the past to Earth, projected on an exotic surface covered in B rays.

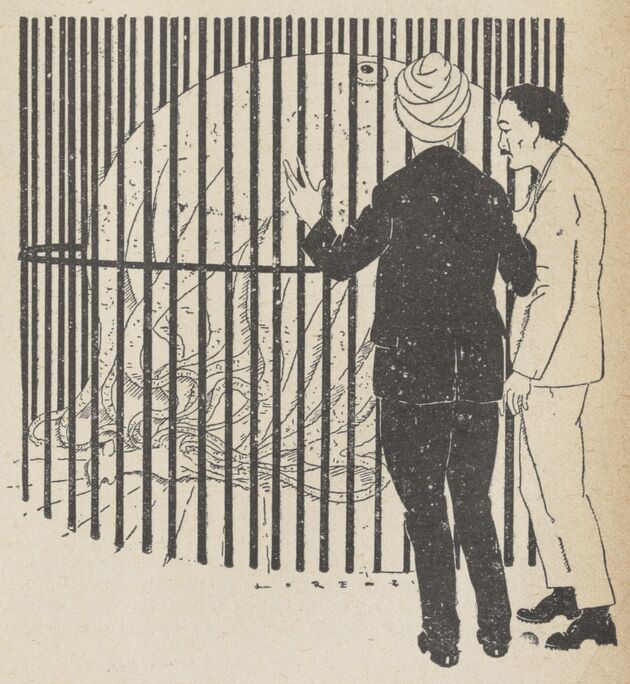

Jean de Quirielle, Le voleur de cerveaux, [The brain thief], illustrated by Fabio Lorenzi, in Lectures pour tous, 1920

Between 1909 and 1929, Lectures pour tous published several short stories by Octave Béliard, by Maurice Renard, by Raoul Bigot, by Noëlle Roger and by J.-H. Rosny Snr. These stories are scattered with scientific extrapolations. Éther-Alpha by Albert Bailly, recipient of the Jules Verne prize, presents a transparent space ship made from ether, Le sommeil sous les blés by Joseph Jacquin and Aristide Fabre speculates on the anabiosis of Fakirs, while Le voleur de cerveaux by Jean de Quirielle stages a scary creature with tentacles, which feeds on psychic energy.

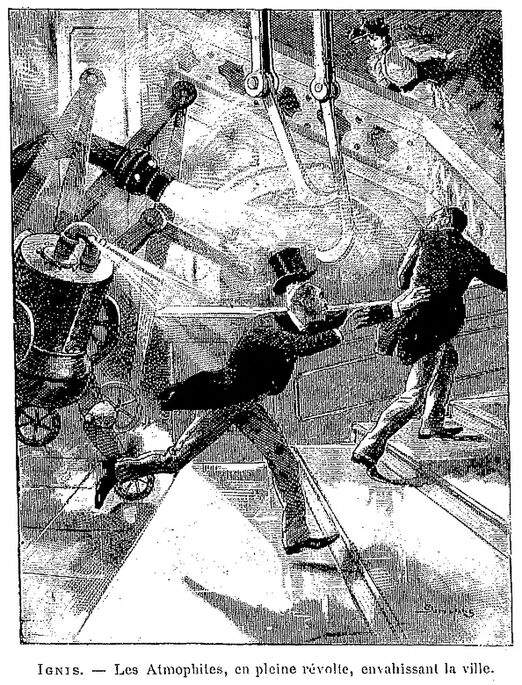

Let us also mention the Journal des Voyages et des Aventures de Terre et de Mer (1877-1949), sub-titled « revue de récréation scientifique » (scientific recreation review), founded by Charles-Lucien Huard, as well as Sciences et Voyages (1919-1939) created by the Offenstadt brothers, who each published stories in installments that could be classified as belonging to the “merveilleux-scientifique” genre, amongst articles of scientific popularization or travel accounts. The “merveilleux-scientifique” plot is often hidden behind multiple twists. In this way, L’âme du docteur Kips by Maurice Champagne imagines that the hero reincarnates in another location on Earth, under the actions of a Fakir. Finally, between 1887 and 1905, La Science illustrée, a journal founded by Louis Figuier, published scientific articles, scientific novels or amusing science articles. Under the guise of a fast-paced scientific adventure, published under the label of “scientific novels”, authors such as Louis Boussenard or Count Didier de Chousy told of experiments on artificial creations of life, or futuristic towns inhabited by helpful machines, the Atmophites, who rose against their masters.

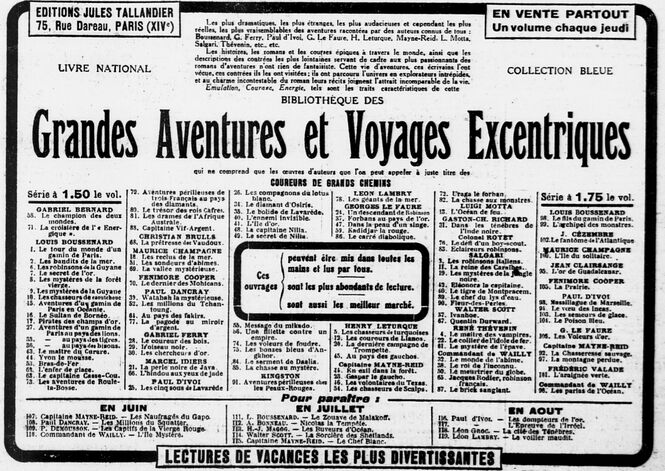

Next to these magazines and periodicals, four publishers distinguished themselves by the recurrence of their authors, by the coherence of their catalogue and the attention paid to the covers : Albert Méricant, Jules Tallandier, Joseph Frenczi and Pierre Laffitte.

Between 1908 and 1909, Albert Méricant published the « Le Roman d’Aventures » (adventure novels) collection, recognizable by their red frames, several works by Gustave Le Rouge and Paul d’Ivoi. The “ Les Récits Mystérieux” (mysteries) collection, which was published between 1912 and 1914, is the one that is closest to a special collection, as the majority of its 21 volumes are mostly to do with conjecture (namely Léon Groc, Jules Hoche, Jean de Quirielle, Gustave Le Rouge) and offer stories of artificial life, psychological hold and intra-atomic forces. These publications distinguished themselves by bright coloured covers, mostly designed by the painter Charles Atamian.

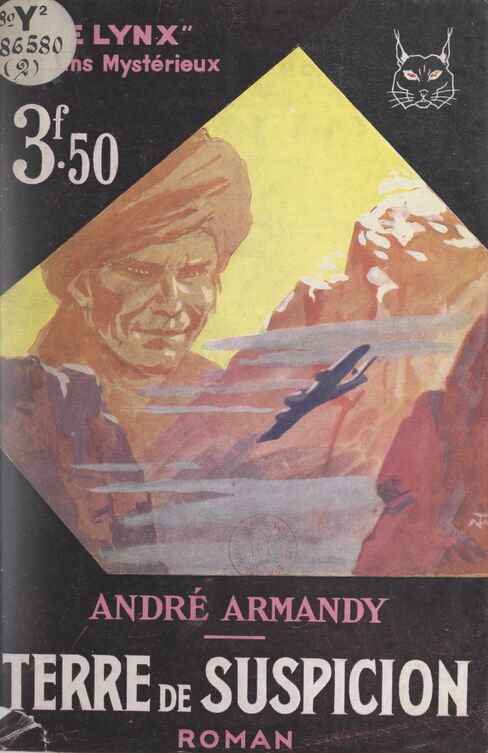

Tallandier published numerous adventure novels, in the « Bibliothèque des Grandes Aventures » collection, illustrated by Maurice Toussaint, in the years 1927 and 1930 (Cyrius, Norbert Sauvestre, Paul d’Ivoi, Louis Boussenard, René Thévenin). In the years 1939-1941, the « Le Lynx» collection, framed in black , republished under new titles, novels by H.J. Magog, by André Couvreur or even by Léon Groc.

André Armandy, Terre de suspicion, book cover by Maurice Toussaint, « Les Romans Mystérieux », Paris : Jules Tallandier, 1926

Again, publisher Pierre Lafitte, in the collection « Idéal-Bibliothèque» that began in 1910, with its yellow frame, published stories by Clément Vautel and by Maurice Renard, including his Homme truqué. The detective collection “Point d’interrogation” that was launched in 1932 with Gaston Leroux’s famous Mystère de la chambre jaune , also contained conjectural writings by Maurice Leblanc. To finish, prolific publishers J.Ferenczi and Sons had many of their covers illustrated by Henri Armengol . They dedicated a collection exclusively to Guy de Téramond, named “Les romans de Guy de Téramond”, and published “merveilleux-scientifique” fiction in their collections named “Les Grand romans”, “Voyages et Aventures”, “Le Livre de l'Aventure”, “Le Petit Roman d’Aventures”, “Les Dossiers Secrets de la Police”…

The review of publications that participated in the spread of « merveilleux-scientifique » literature doesn’t stop there, and goes way beyond French historic collections. Translations could indeed be found in Italy, Great Britain, in the Czech Republic, in Russia and in Spain, sometimes only months after the original French version was published. The Italian periodical Il Romanzo Mensile translated more than 26 “merveilleux-scientifique” stories between 1908 and 1933. It was a local illustrator, Riccardo Salvadori, who reinterpreted some of the key-texts of the corpus, from L’homme truqué by Maurice Renard to L’homme qui voit à travers les murailles by Guy de Téramond. In this sense, the fact that the school of “merveilleux-scientifique” was progressively forgotten to the advantage of Jules Verne, Albert Robida or American authors, can partly be explained by its incapacity to build a remarkable collection worthy of its name, or a comparable movement to American science-fiction. However these texts shone well beyond French borders.

Translated from French by Claire Carolan